|

The Danish Vocational Education and Training System. 2nd edition

Resumé This publication describes the Danish VET system and how it is geared to meet the continuous challenges of a globalising world:

Contents:Complete table of contents Ministry of Education © Ministry of Education 2008

Table of content

Preface

PrefaceIn Denmark, there is great political attention on vocational education and training (VET) as a key to achieving major political goals. Like in the rest of the EU, VET plays a key role in implementing the strategy for lifelong learning, and is an integral part of promoting the achievement of the Lisbon and Barcelona goals. The Copenhagen Process1 provided an overall framework for European VET development, and contributed significantly to raising awareness of the importance of VET in ensuring the EU a competitive advantage – compared to the economies of the US and Asia – by bridging economic development and social cohesion. The challenges of globalisation are major drivers behind the political concerns on VET. Economic globalisation and technological development increase competition among nations, but also lead to new forms of global specialisation and collaboration. These days, production is split into chain processes. Innovation and design may take place at the headquarters in Copenhagen, production in China, IT support and development in India and services in Ireland. In this respect, globalisation may lead to a polarisation of society: many of the unskilled and low-skilled jobs are moving from the West to the East and the developing countries. The number of unskilled jobs in the private sector in Denmark has dropped by 15% since 1980. However, approximately one quarter of the population2 have no skills beyond basic schooling. This poses a major challenge which requires an all-inclusive VET system that is able to ensure an adequate level of education in Denmark and prevent social exclusion in the longer term. Danish VET is organised according to the dual principle meaning that 1/2–2/3 of a VET programme takes place in an enterprise. A large number of stakeholders, among these politicians, public managers, social partners, enterprises, vocational colleges, and teachers’ unions share responsibility for developing the system. It is a diverse and complex area which is embedded in different policy areas: the economy, employment, education, social integration and business development, so the VET system must meet a number of different objectives:

The aim of this publication is to describe the VET system in Denmark, and also to offer an insight into how the system is geared to meet the continuous challenges of a globalising world.

Søren Hansen Facts about DenmarkDenmark is a small country with a surface area of 43,000 square kilometres (excluding Greenland and the Faroe Islands). With a total population of 5.4 million inhabitants, the country is densely populated. The majority of the population lives in towns or cities, with only 15% living in rural areas. In contrast to many other countries, Denmark’s population is relatively homogeneous – only 9% have a foreign background. Denmark is a constitutional monarchy with a representative democracy. The Danish Constitution (Grundlov) was adopted in 1849 and was last amended in 1953. The Danish Parliament has only one chamber, the Folketing, which has 179 members, including two elected from the Faroe Islands and two from Greenland. Elections are held using the proportional representation system, and the government is formed from the Folketing, which is elected for a four-year term. However, the government can dissolve the assembly at any time and announce new elections. Denmark has three levels of government. The central administration is based in Copenhagen and consists of the various ministries, which may have one or more departments and comprise a number of institutions. The country is divided into five regions (regioner) and 98 municipalities (primærkommuner). Footnotes1) The Copenhagen Declaration was adopted by 31 European Ministers of Education under the Danish EU Presidency in 2002. The aim was to strengthen European cooperation in the field of VET.2) Facts and Figures 2007. The Danish Ministry of Education, 2008.

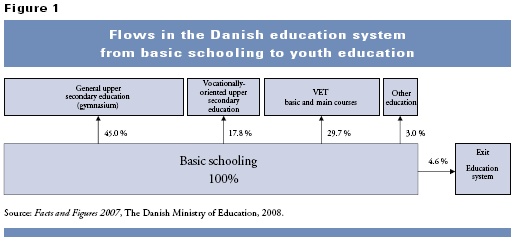

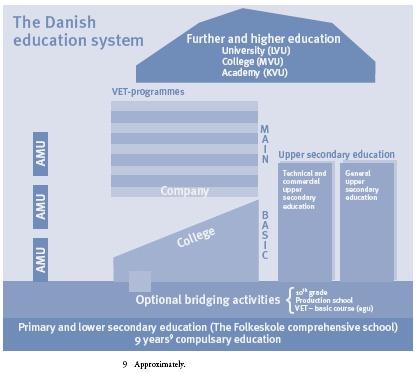

Introduction to the Danish VET systemThe Danish VET system is part of the overall youth education system and aims at developing the general, personal and vocational skills of young people. The overall objectives of VET are laid down in the Act on Vocational Education and Training3. According to this, the aim of the programmes is not only to provide the trainees with vocational qualifications, which are formally recognised and in demand by the labour market, but also to provide them with general and personal qualifications that open up the trainees’ possibilities for lifelong learning and for active citizenship. The system is based on three main principles:

A definition: Facts and figures about VET in Denmark Approximately one third of a youth cohort enrols in a VET programme after basic schooling (2007). There is a decrease in the number of young people who enter a VET programme as the trend is currently for young people to opt for the more academically-oriented upper secondary education programmes. The most popular programmes are the commercial, building and construction, technology and communication, and the social and health care programmes. The drop-out rate is high. Only around 70% complete the basic course and 80% complete the main course. Many of the trainees who drop out continue in other VET programmes or in the general upper secondary education programmes. Nonetheless, 40% of all dropouts are estimated not to continue any education or training programme within the next ten years. The dropout rate is higher among men than women and higher among immigrants than among those with Danish origin. In general, drop-out rates are a major problem in the Danish VET programmes, and reducing the number of trainees dropping out, especially in technical training, is an important political priority. Approximately 80% of those completing a VET programme enter the labour market and are employed in a company one year after completion. The number of male trainees in VET is, on average, marginally higher than the number of females trainees: with 55% male trainees and 45% female trainees. However, gender distribution is uneven among the various programmes, e.g. within the social and health care programmes, female trainees constitute 93%, whilst within traditionally male sectors, such as mechanical engineering, transport and logistics, they constitute only 4%. The average age of trainees on the basic courses was 21 in 2005. For the main courses, the average age was 26. In 2005, one out of ten trainees were immigrants or from ethnic minorities. Danish VET is characterized by four objectives: to be an involving, flexible, inclusive and developing system. In the following chapters 2-5, these four objectives are further elaborated.

Source:

Footnotes3) The Act on Vocational Education and Training LBK no. 561 of 06/06/2007.

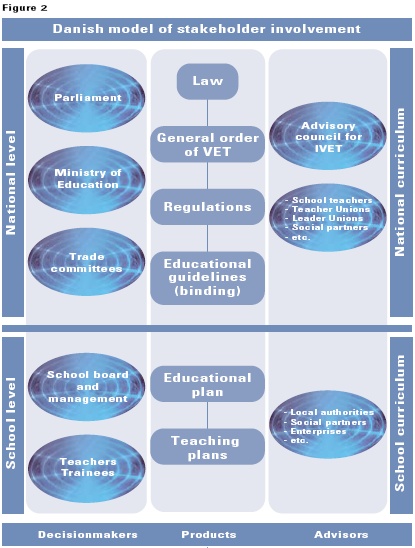

An involving systemThe Danish VET system is characterised by a high degree of stakeholder involvement. Not only the social partners, but also colleges, enterprises, teachers and trainees are involved in a continuous dialogue about, and development of, the Danish VET system. The cooperation between the Ministry of Education and the social partners is very well developed, and the vocational colleges and the enterprises also share responsibility for the training of each individual trainee – all of which ensures that the qualifications obtained are well-known and generally recognised in the labour market. The involvement of stakeholders creates a system based on consensus and a system in which responsibilities are shared within clearly defined boundaries.

The Ministry of EducationThe Minister of Education is responsible for the general education policies and for ensuring that the VET programmes are consistent with these policies. In regard to VET, the Ministry lays down the overall objectives for the VET programmes and provides the framework within which the stakeholders, i.e. the social partners, the vocational colleges and the enterprises, are able to adapt the curricula and methodologies to the needs of the labour market and of the trainees. The Ministry is responsible for ensuring that the VET programmes have the breadth required for a youth education programme and for the allocation of resources. The Ministry is furthermore responsible for approving new VET qualifications on the basis of recommendations from the Advisory Council for Initial Vocational Education and Training (Rådet for de Grundlæggende Erhvervsrettede Uddannelser – REU), and for approving the colleges that are to provide the basic and main courses in VET. It is also the Ministry which lays down the overall rules for VET – in cooperation with the REU – and draws up the regulations on the individual VET programmes – in cooperation with trade committees (please see The social partners, page 17). The regulations are supplemented with guidelines drawn up by the trade committees and issued by the Ministry (please see Facts about the national legislative framework, page 26). Finally, the Ministry is responsible for inspection and quality assurance, which are issues gaining in importance. The introduction of new steering principles, such as framework governance and decentralisation in 1991 (please see Reform 1989, page 41), which granted providers greater autonomy with regards to adapting VET provision to local needs and demands, accentuated the need to implement national quality approaches which, on the one hand, supported decentralisation, and on the other hand, ensured central control with the quality of VET provision. The social partnersOne of the main characteristics of the system is the active participation of the social partners at all levels of the system. This guarantees that the content of the individual VET programme meets the demands of the labour market and that the qualifications are recognised by business and industry. The social partners are represented in a number of councils and committees acting at local, sectorial and national levels. The Advisory Council for Initial Vocational Education and TrainingThe Advisory Council for Initial Vocational Education and Training (Rådet for de Grundlæggende Erhvervsrettede Uddannelser – REU) comprises 25 members from the social partners, the school leader and teacher associations as well as a number of members appointed by the Ministry of Education. The chairperson is appointed by the Minister of Education. The aim of the REU is to advise the Ministry of Education on all matters concerning the VET system. It is responsible for monitoring labour market trends and on this basis recommending the establishment of new VET qualifications, the adaptation of existing ones or discontinuation. It is also responsible for monitoring existing programmes and, based on its findings, for making recommendations for better coordination between programmes or the merging of programmes. The REU concentrates on general national issues concerning VET provision in Denmark. The trade committeesThe national trade committees (de faglige udvalg) provide advice on specific VET qualifications relevant to their sector and on the content, structure, duration and evaluation of programmes and courses. Employers and employees are equally represented in the trade committees. Each committee is responsible for one or more VET qualifications. In 2008, there are approximately 120 trade committees. One of the main objectives of involving the social partners is to ensure the relevance and quality of VET programmes in relation to the labour market. The trade committees are responsible for the continuous adaptation and development of the VET programmes. The committees monitor the skills development in the labour market and, on that basis, recommend changes to existing programmes. They may also recommend the establishment of new VET programmes or the discontinuation of out-dated VET programmes. The role of the social partners is to ensure that VET matches the needs and demands of enterprises and of the labour market at both national and local levels. Another important aspect of the trade committees’ scope of work is the approval of training places. The trade committees are responsible for approving and inspecting enterprises that want to take on trainees on the basis of defined criteria. In order to be approved, an enterprise must have a certain level of technology and a variety of tasks to be performed that will ensure the trainee a full range of activities and tasks corresponding to the qualification requirements of a skilled worker. Finally, the trade committees are responsible for the journeyman’s test and for issuing certificates to trainees (technical training). The trade committees set up their own secretariats with their own budgets, funded by the social partners themselves. The secretariats are responsible for the day-to-day administration and service the social partners by drawing up analyses, preparing case work, initiating courses for external examiners, etc. The local training committeesThe local training committees (de lokale uddannelsesudvalg) assist the vocational colleges in the local planning of the programmes. They provide advice on all matters concerning training and are responsible for strengthening the contact between colleges and the local labour market. The local training committees consist of members representing the organisations represented on the national trade committees. They are appointed by the trade committee upon recommendation from the local branches/affiliates of the organisations. The local training committees also include representatives from the college, the teachers and the trainees. The local training committee acts as advisor to the college in all matters concerning the VET programmes within their jurisdiction and, furthermore, promotes cooperation between the college and the local labour market. In the VET programmes, there has traditionally been a division of labour between the Ministry of Education and the social partners: the Ministry is responsible for the school-based part of the training and the social partners for the work-based part. ProvidersThe VET programmes are provided by vocational colleges and enterprises. CollegesThere are five types of colleges:

The colleges provide not only VET, but also short-term higher education (korte videregående uddannelser – KVU) and adult vocational training. Furthermore, the commercial and technical colleges provide vocationally-oriented technical and commercial upper secondary education programmes (htx/hhx) that qualify for both employment and admission to higher education. In 2008, there are 115 vocational colleges nationwide providing VET programmes. The colleges are approved by the Ministry of Education to provide specific basic and main programmes. Approval is given on the basis of two considerations: the aim of building sustainable VET environments and the aim of ensuring the geographical dispersion of VET. The colleges are independent public institutions with their own board of governors. The majority of the members must reflect the working areas of the college. Employers’ and employees’ organisations must be represented in equal numbers and must represent the geographical area or the sectorial areas of the college’s VET provision. In addition, the teachers and trainees of the college are represented on the board. The colleges have relative autonomy vis-à-vis the budgeting, organisational and pedagogical strategies and the local planning of the VET programmes. The colleges are responsible for the local planning of the VET programmes in cooperation with the local training committees. The content of the training is laid down in a local education plan, corresponding to the general regulations and guidelines for the specific VET qualification. The overall elements of the local education plan are laid down in the Act on Vocational Education and Training, which stipulates, for example, that the local education plan must include a description of the pedagogical, didactical and methodological principles for the training, including a description of how the trainees are involved in the planning and implementation of teaching. The local education plan must also include descriptions of teacher qualifications, technical equipment, cooperation between the college, the trainees and the enterprises, the personal education plan and logbook, etc. EnterprisesPractical training takes part at an enterprise which has been approved by the relevant trade committee. The enterprises can be approved to be responsible for the whole training period or for part of the training period. In order to be approved, an enterprise must have a certain level of technology and must be able to offer the trainee a variety of tasks, which ensures him/ her qualifications corresponding to those of a skilled worker in the chosen occupation. The companies are represented at national level, via their employers’ organisations, at local level in the local training committees and in the boards of directors of the local vocational colleges. In both VET and CVET, the enterprises are able to “colour” the local education plans/CVET courses so that they meet the specific needs and demands of the local or regional labour market. TraineesThe trainees also play an institutionalised role in the Danish VET system. Pursuant to the Act on Vocational Education and Training4, the trainees are able to influence both their own training and the general school environment. This is done by involving the trainees in the planning of the teaching and training. In the day-to-day training activities, the teachers may involve trainees in laying down overall themes for a specific subject, or by letting them choose between different assignments (this is also part of the overall differentiation of teaching). Via student councils and the trainees’ representation on the board of governors, the trainees have the possibility of voicing their opinions. The trainees have a decisive influence not only on their own training but also on the colleges’ provision of education and training by means of their educational choices and the description of their learning pathway in their personal education plans. Furthermore, the Ministry of Education initiates surveys among the trainees, for example in connection with major reforms, whereby the trainees are able to provide feedback on national VET policies.

Footnotes4) Act on Vocational Education and Training LBK 561 of 06/06/2007.

A flexible systemThe Danish VET system is a highly flexible system, offering a wide range of options for the trainees – both in terms of time and in terms of contents. It is a system in which the needs and demands of both trainees and enterprises should be fulfilled. The flexibility concerns the framework, the structures, and the contents of VET. Adding to the flexibility of the system is the introduction of assessments of prior learning (APL5) (in Danish: realkompetencevurdering). All trainees have their prior learning assessed before a personal education plan is drawn up. The Danish system is committed to a far-reaching form of flexibility, where individualised learning pathways are drawn up by the trainees, who themselves shape the pace and the content of their own training; a highly flexible, competence-based VET system, where the trainees can take one step of a vocational qualification at a time. Flexible frameworkThe legislative framework for the Danish VET programmes is highly flexible. It is a decentralised system with an overall management principle of “management-by-objectives”. The overall objectives and framework for VET are drawn up at national level, and the colleges, the enterprises, and the trainees are relatively autonomous within this framework. The framework is flexible in regard to the funding and allocation of resources: the colleges receive taximeter grants per trainee, leaving them with the responsibility of detailed management, budgeting and daily operation; hereby promoting a more demand-led VET system in which the colleges compete on provision and quality. The national curriculum is a framework curriculum, giving vocational colleges, enterprises and trainees the possibility of adapting VET to local and individual needs and demands. The primary objectives and the framework rules must be met, but the specific content of the training may vary from college to college and from trainee to trainee. However, although the framework is flexible, the outcome is fixed: nationally recognised qualifications. The system of management-by-objectives can be divided into four levels, each with its own rules, procedures and instruments for managing-by-objectives: the political level, which has the overall responsibility for drawing up the framework and ensuring the necessary resources, the social partners, which are responsible for developing the VET system and the individual VET programmes, the providers, which are responsible for planning and providing the VET, and the trainee, who is responsible for his/her own training pathway.

Facts about the national legislative framework

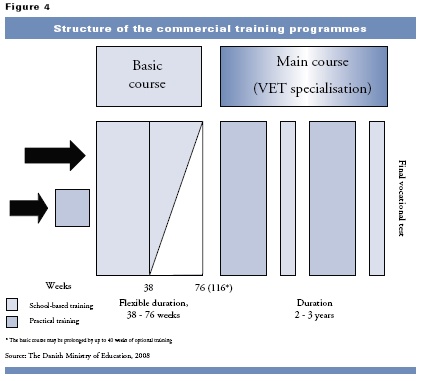

In addition to these main acts, all VET programmes are regulated by a specific regulation on the VET programme, stipulating the duration, contents, subject, competence levels, etc. and by a set of guidelines detailing the objectives, duration, structure, subjects, competences, examination requirements, credit transfer, quality assurance, etc. The guidelines were introduced in 2001 in order to simplify the system and to ease the changes in individual VET programmes. These days, the programmes can be continuously adjusted as long as they adhere to the guidelines. This is done on an annual basis, in cooperation between the Ministry of Education and the trade committees. Flexible structuresThe main principle in the Danish VET system is that of dual training, whereby training alternates between education and training in a vocational college and in-company training. This dual training principle is both a pedagogical principle and an organisational-institutional principle, which makes demands on both the pedagogical planning of the programmes and on the cooperation between the colleges and the enterprises. The coordination between school-based and work-based learning constitutes a particular challenge for all the stakeholders in the system, as it is a key factor ensuring coherence in the programmes. Although the dual training principle has been debated animatedly over the past couple of years, it is important to bear in mind that it ensures a smooth transition from training to the labour market. People who have completed a VET programme have an employment rate of approximately 80% one year after completion of their training, which is a strong indicator of a well-functioning system. There are two access routes to the VET programmes: the school pathway and the company pathway. Trainees can either enrol on a basic course or start in an enterprise with which they have a training contract. In both cases, school periods (1/3-1/2 of the entire training programme) will alternate with periods of in-company training (1/2-2/3). The VET system encompasses programmes of durations from 18 months to 5.5 years that are divided into two parts: a basic course, which is broad in its scope and a main course, in which the trainee specialises within a craft or a trade. There are 12 basic courses:

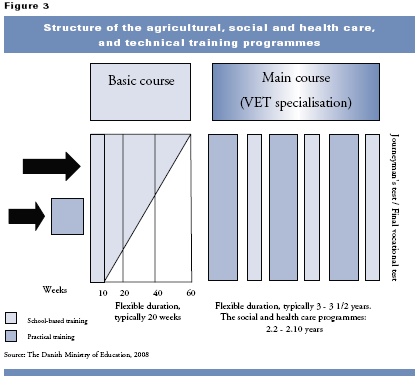

The basic courseIn the agricultural, social and health care, and technical training programmes, the basic course, particularly for the technical training programmes, is highly flexible in terms of both time and contents. The basic course consists of both compulsory and optional subjects. The optional subjects provide the individual trainee with the possibility of acquiring additional qualifications in regard to either the main course or to gain access to further or higher education. The length of the basic course in the technical training programmes will vary from programme to programme, and from one trainee to the next, depending on their qualifications, requirements and needs. The basic courses typically last 20 weeks but may last up to 60 weeks, depending on the proficiency level, requirements and needs of the individual trainee. The basic course of the commercial training programmes is not yet as flexible as that of the other VET programmes. The trainees normally enter via the school pathway and attend a basic course lasting 76 weeks. However, the intention is for the basic course to become more flexible: the introduction of APL, the “toning” of basic subjects (please see Flexible curriculum, page 33) and the introduction of specialist subjects earlier in the basic course have opened up for increased flexibility, which will constitute a major challenge to the commercial colleges in the coming years. Most trainees enter VET via the basic course and then apply for an apprenticeship once they have completed the course. Everybody who has completed basic schooling can be admitted to the basic course; but a contract with an enterprise is required in order to continue on the main course. The selection of trainees for apprenticeships is carried out on market terms, i.e. the trainee writes an application and goes to a job interview in competition with other trainees. The trainee and the enterprise then enter a binding contract (with a three-month trial period) and the trainee receives wages according to the collective agreement within the sector. During school periods, the enterprise receives compensation from the Employers’ Reimbursement Scheme (Arbejdsgivernes Elevrefusion – AER). This scheme was set up by law in 1977 and is financed by contributions from all employers. Provision of a sufficient number of apprenticeships is of utmost importance to guarantee the trainees within VET an opportunity for practical in-company training and to secure sufficient numbers of qualified skilled workers for companies to employ. Therefore, it is necessary to develop apprenticeship contracts so that they reflect developments within the companies. For example, it is now possible to make an apprenticeship contract for only part of the programme, providing an opportunity for the companies with relatively short term production plans or companies with a specialised production to employ apprentices. If a trainee cannot obtain an apprenticeship, he or she can enrol in school-based practical training. Some 50 VET programmes offer school-based practical training, of which approximately 10 programmes have restricted intake. Through the educational guarantee, the trainees are always guaranteed that they may complete at least one of the programmes within the specific basic course.

The main courseIn the agricultural and technical programmes, the main course normally lasts between 3 and 3 1.2 years, of which the schoolbased part constitutes approximately 40 weeks. The social and health care programmes are shorter: the social and health care helper takes 1.2 years to complete and the social and health care assistant 2.10 years to complete. Most main courses are divided into fixed periods of school-based and work-based training. The aim is to ensure progression in the programmes and coherence between the learning taking place in school and the learning taking place in the enterprise. During the school periods, the trainees meet with other trainees at the same competence level and take part in learning activities at a vocational college. Normally, the periods in school last from one to five weeks. The programme is concluded with either a journeyman?fs test or a final project-based examination, in which the trainee is required to show that he or she has acquired the skills necessary to work as a skilled worker within his/her trade. Flexible in time and contentFlexibility in time and content is concretised in the personal education plan and in the flexible curriculum. The personal education planWhen a trainee enters a VET programme, a personal education plan will be drawn up. In the education plan, the trainee is required to describe his/her pathway from unskilled to skilled worker: the objectives, how to achieve the objectives, learning activities, etc. The education plan is drawn up together with a so-called contact teacher (tutor) from a vocational college, and the contact teacher is also responsible for assessing the trainee’s prior learning and taking the trainee’s “real” qualifications into consideration. Thus, every trainee in a VET programme will have drawn up an individual learning pathway. The trainee is actively involved in drawing up the personal education plan and is expected to take responsibility for his/her own learning. The assessment of the trainee’s prior learning contributes to the principle of lifelong learning, which has been an allencompassing priority in the Danish education system. The assessment is also a way of ensuring coherence between the VET system and the continuing and further education and training system. The VET programmes also aim to provide the trainees with learning skills as well as a foundation for continuous and further education and training. The personal education plan is entered into the national web tool called “Elevplan”6 (Trainee Plan). Elevplan contains all the trainees’ personal education plans and electronic logbooks with various papers and notes from the college, etc. A “scorecard” is drawn up on the basis of the personal education plan, showing the trainee’s progress towards reaching the overall objectives for the training. The system shows trainees the various learning activities offered by the colleges, and allows them to enrol online. The trainee can also see his/her timetable and absenteeism rate. When the trainee starts training in an enterprise, the enterprise has access to all the relevant parts of the trainee’s personal education plan and is able to see when the trainee is going back to school, etc. Moreover, the enterprises are expected to enter into a dialogue with the vocational college and the trainee. The aim is for all enterprises to describe the practical training and its objectives in the same way, thus considerably improving the possibilities for coordination between enterprise and college as well as for progression in the training. Flexible curriculumA VET programme consists of four types of subjects: Basic, area, specialist and optional subjects, which are selected and put together by the trade committee. Basic subjects consist of theoretical and practical teaching aimed at providing the trainees with broad vocational knowledge and skills, whilst at the same time contributing to the personal development of the trainees or their understanding of different societal trends. The basic subjects are provided at different levels (F –> A). Area subjects are subjects which are common to one or more VET programmes, while specialist subjects are specific to a single VET qualification. Specialist subjects are subjects at the highest level of a VET programme and aim to provide the trainee with specific vocational competency. Finally, there are optional subjects, which are aimed at meeting the interests of the trainees. Up until 2003, the national regulations stipulated that there had to be a specific distribution among the subjects, but now there is more flexibility – not only within and across VET programmes, but also from trainee to trainee, depending on the goals which have been laid down in their personal education plan. Footnotes5) Here used as an equivalent to the EU terms of identification, recognition and validation of formal, non-formal and informal learning.6) http://www.elevplan.dk

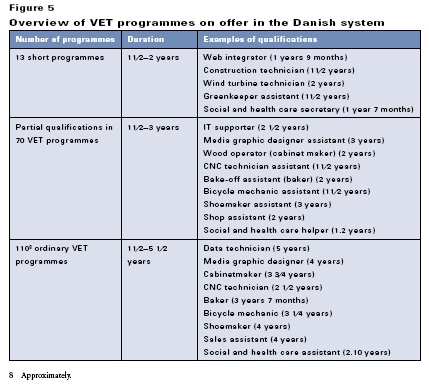

An inclusive systemOne of the main policy concerns has been to reduce the dropout rate from the VET programmes and to make VET a very inclusive system, attracting both “strong” and “weak” learners. As in many other countries, there has been a general trend for more young people to go into general upper secondary education programmes. For this reason, efforts are being made to improve the image of the VET system so that it is not merely an attractive choice for “weak” learners. Attempts have been made to solve this problem by creating a highly individualised system where trainees have wide-ranging possibilities for drawing up their own education plans, laying down their own objectives and having their prior learning recognised. In order to make the system even more inclusive, a number of alternative routes to partial qualifications, or more practically-oriented qualifications, have been drawn up. Finally, policy initiatives have focused on vocational proficiency levels and standards. Some VET programmes, e.g. those in commercial training, have been met with sectoral demands for higher vocational proficiency levels in order to ensure progression in the programmes (from the basic to the main course), and hereby improving the overall level of competency. Practically-oriented young peopleThe report from the inter-ministerial working group concerning more practical access routes to VET7 introduced a new typology of young people: the practically-oriented young people. This group was defined on the basis of the PISA surveys and results showing that a considerable group of young people had very poor basic skills in literacy, numeracy, and writing. As a consequence, this group has problems completing a youth education programme. The survey showed that especially children of immigrants and refugees had poor basic skills. Approximately 60% of all young people from ethnic minorities drop out of a VET programme due to proficiency problems. The “practically-oriented young people” can be defined by three characteristics: they have learning disabilities, social problems and cultural problems. Furthermore, they make very high demands on education and have unrealistic expectations as to what and how fast they can learn. Very often, their basic schooling has been a bad experience, so it is difficult for them to complete a VET programme. For this reason, a number of initiatives have been launched to provide this very diverse target group with suitable, more practical alternatives in VET. These include a project testing the framework for the flexible VET programmes; better possibilities for disseminating the training places that are available among trainees searching for one (http://www. praktikpladsen.dk); and establishing Danish as an optional second native language subject for ethnic minorities at the colleges. Furthermore, a number of alternatives or supplements to the ordinary route have been established that prioritise practical training, e.g. short VET programmes, partial qualifications, apprenticeship pathway, pre-training, (EUD+) and additional qualifications. Short VET programmesThe short VET programmes were launched in 2005. The aim of the programmes was to offer an alternative to the practicallyoriented young people and to ensure their employment after the completion of a programme. The programmes are therefore targeted at sectors where the possibilities of employment are good, and where there is a need for both short specialised qualifications and “ordinary” qualifications. The demand for skilled workers with short specialised qualifications is increasing in certain industrial sectors, such as the retail and butchering trades. Partial qualificationsIn the main part of the VET programmes, partial qualifications have been drawn up by the trade committees. Partial qualifications are directed at trainees who may not have the skills or the patience to obtain full vocational qualifications. Approximately 70 out of 110 VET programmes offer partial qualifications. The partial qualifications correspond to current job profiles. The partial qualifications offer trainees the possibility of acquiring part of a qualification and thus also the possibility of completing the qualification later. The partial qualification is completed with a test and a certified partial qualification. The division of the programmes into partial qualifications is related to the ongoing development of a national qualification framework, corresponding to the European Qualification Framework (EQF). The apprenticeship pathwayThe trainees may choose an apprenticeship pathway (mesterlære) into VET. The apprenticeship pathway constitutes an alternative, especially for practically-oriented trainees who are tired of school. In the apprenticeship pathway, the entire basic course is acquired by means of in-company training. The trainees will be able to acquire suffient competences to start on the main course after having completed the first year of their apprenticeship. The elements of in-company training, and the objectives to be atttained, will be described in the personal education plan for the individual trainee. The education plan constitutes an important binding element for all stakeholders (the college, the enterprise and the trainee). The college and the enterprise are responsible for guiding and counselling the trainee and for evaluating the competences acquired by the trainee during the in-company training in order for the trainee to access the main course. The trainees will be able to take the basic subjects required both during the apprenticeship (within the enterprise or at a college) and during the main course. The apprenticeship pathway is concluded with exactly the same examinations and tests as trainees who have taken the school or company pathway, thus ensuring that the competences mastered at the end are the same for alle trainees, regardless of how they have been attained. In this regard, the apprenticeship model is one step closer to the entirely competence-based system, where it is less important how and where the competences have been acquired.

Pre-trainingYoung people (15-18 years old) may start in pre-training in an enterprise for a period of 3-6 months in order for both young persons and enterprises to “size each other up”. After a short introducation period, the trainee participates in the production processes within the enterprise. The contract entered into by the enterprise and the trainee is binding after a three-month trial period. If any of the parties want to terminate the contract after the trial period, it has to go through legal negotiations in the trade committee. The pre-training model aims to provide an option with less commitment for both enterprises and young people. EUD+In 2005, it became possible for trainees under the age of 25 to complete a VET programme as part of the EUD+ scheme. This option allows a trainee to complete a basic course and the first part of a main course, either in a company or in the compensatory practical training scheme. Afterwards, the trainee has to be employed in a company and have at least six months of ordinary employment in order to obtain relevant qualifications. If the trainee then wants to continue on the next part of the VET programme, he or she has to have his/ her qualifications assessed at a vocational college and a personal education plan must be drawn up, describing the learning activities, employment and/or practical training he/she has had at school or in the company. The EUD+ scheme is completed without any educational contract and is provided by those colleges that are approved to provide the main courses. The EUD+ scheme is targeted at the practically-oriented young people, providing them with the possibility of acquiring full qualifications at a later stage. Additional qualificationsThe Danish VET system seeks to provide direct access to the labour market and also to offer trainees access to further and higher education. This enables trainees to add academic qualifications to their vocational qualifications. Trainees wanting to follow courses at a higher level, for instance within the vocationally-oriented upper secondary education programmes (hhx/htx – higher commercial and technical examination), can do so either by prolonging their basic course, by being exempted from other subjects (in case of APL) or by taking extra courses during the main course. The aim of taking an additional qualification is to ensure access to further and higher education. Some VET programmes may serve as an entry into specific education programmes at tertiary level (e.g. architect or designer).

Footnotes7) Rapport fra den tværministerielle arbejdsgruppe vedrørende praktiske indgange i flere uddannelser, the Danish Ministries of Finance, Education, Employment and Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs, 2005.

A developing systemThe Danish VET system is undergoing continuous change due to the pressures of globalisation, including the enhanced cooperation and compatibility of VET policies in Europe. Over the past 15 years, the pace of reform has intensified. The overall aims of these reforms have been

A brief outline of the major reforms and the elements thereof from the late 1980s to present time is provided below: Reform 1989In 1989, a major reform of the VET system was adopted by the Danish Parliament. The reform introduced new overall steering mechanisms in the VET system. Instead of fixed national rules and curricula, the colleges were to operate within a system of management-by-objectives. The new regulations and guidelines on VET became framework regulations, and the colleges now had to draw up local education plans and adapt them to the needs of local industry and the local labour market. The overall aim was to make the VET system more responsive to changes in technology, production and the way work was organised. The new system changed the status of the vocational colleges. They became independent public organisations, and instead of a fixed budget, their finances were now based on a combination of fixed grants and taximeter rates based on trainee intake and completion rates. The intention was to make the colleges more market-oriented, more competitive and more professional in their overall management. Granting the providers greater budgetary control and greater autonomy with regard to adapting VET provision to local needs and demands accentuated the need to implement national quality approaches in order to ensure the homogeneity of national provision and maintenance of national standards. The reform of 1989 changed the entire institutional and administrative set-up of the VET programmes. In addition, the 1989 reform was a pedagogical reform that introduced the pedagogical principle of interdiciplinary and holistic teaching. Reform 1996 – commercial trainingIn 1996, the objectives, framework and content of the commercial training programmes were reformed. The main aim of the reform was to make the programmes more flexible and more competence-based. Six areas of commercial competency were defined: personal; economic; communicative and technological; commercial and service; international and cultural; and societal competencies. It was new, and difficult, for the commercial colleges to plan competence-based training activities. The reform was the first step towards the reform of the technical training programmes which was implemented in 2000: more flexible access routes were introduced (please see Reform 2000, page 43); interdisciplinary and holistic teaching was further strengthened, including new elements, such as SIMU enterprises, and the focus was on the individual trainee and his or her learning processes. Reform 2000In 2000, a major reform of primarily the technical training programmes was implemented. The background for the reform was the fact that technical training did not attract enough trainees, and that a considerable number of trainees dropped out during the training. In order to make the programmes more transparent, more flexible, and more attractive, the structures were changed. Instead of choosing among 83 different VET qualifications from the start of their training, the trainees could now choose between 7 different broad basic courses which are highly flexible and individualised both in terms of time and content (please see Flexible in time and content, page 32). The reform implied major pedagogical changes, putting the vocational teachers to the test in regard to interdisciplinary teaching, team-working, differentiation and coaching. The reform marked the paradigmatic shift from teaching to learning and from focus on the class to focus on the individual trainee. It introduced a number of new elements: the contact teacher, the education plan, the log-book, the possibilities for partial and additional qualifications, etc. (please see page 37 and 39). The reform required quite a cultural change at the colleges to handle the new flexible VET programmes, and the broad basic courses have been criticized for discouraging the students who expect the training to focus on specific vocational skills right from the beginning of the programmes. Act no. 448In August 2003, the VET programmes were adjusted in regard to vocational proficiency and flexibility. The aim of the amendment was primarily to renew the commercial training programmes and to create a common legislation for both commercial and technical training. The commercial training programmes have been criticised for being too theoretical and school-based, so one of the aims was to introduce the vocational specialisation earlier in the programmes. In order to achieve this goal, the rules concerning the basic area, special and optional subjects were changed (please see Flexible curriculum, page 33). The programmes still had to include general educational aspects, but the vocational aspects of the programmes were to be strengthened. This included a vocational “toning” of the basic subjects. Act no. 448 also emphasised the issue of creating a more inclusive system. The programmes were to be flexible enough to be able to include both the trainees who want additional qualifications, by ensuring access to further and higher education, and the trainees who want a partial vocational qualification. The amendment therefore specified that the personal education plan should be based on an APL. Adults in VET had been able to do this via the individual competence assessment (Grunduddannelse for voksne – GVU), but in principle, all trainees in VET should now be assessed individually and have their formal, non-formal and informal qualifications recognised and taken into consideration when drawing up their personal education plans. Act no. 1228In December 2003, another amendment to the Act on Vocational Education and Training was adopted. The aim was to renew the dual training principle and offer especially weak learners the possibility of shorter, more practically-oriented training programmes and established partial qualifications in an existing VET programme. Act no. 1228 also directed focus on increasing the number of training places available and limiting access to the compensatory practical training scheme at the vocational colleges. Act no. 561In June 2007, a more comprehensive amendment of the Act on Vocational Education and Training was adopted, the implementation of which will take place throughout 2008. One of the major changes is the inclusion of the agricultural and social and health care programmes under the same act as the commercial and technical programmes. The purpose is to make the VET system simpler and more coherent. At the same time, the reform meets a need for creating a more dynamic interplay between the sectors (production, trade and service) as one trend is towards qualifications running across the sectors. The main driver of Act no. 561 is the overall political goal that, by 2015, 95% of a youth cohort should complete a youth education programme. This goal has led to a number of minor and major adjustments of the Reform implemented in 2000. The changes encompass both structural and pedagogical changes:

Next stepsThe next steps in developing VET will focus even more on creating and realising the inclusive and flexible VET system which offers individualised training pathways to all kinds of trainees and which leads to qualifications that are recognized internationally. Thus, one of the main tasks is to develop the National Qualification Framework (NQF) in correspondance with the European Qualification Framework (EQF). The numerous reforms take quite a toll on the VET system and managing the diversity and flexibility of the “new” VET system keeps posing quite a challenge for the colleges. Some colleges have come a long way in the process towards a competence-based, flexible and individualised system, whilst others still have a lot to learn. One thing is certain, though, the system will continue to be adapted and changed in order to meet the challenges of a globalising world.

Acronyms

Bibliography

Achieving the Lisbon goal: The contribution of VET, executive

summary, The Lisbon-to-Copenhagen-to-Maastricht

Consortium Partners, November 2004. Relevant institutions and organisations

Government Agencies

Social Partners

Landsorganisationen i Danmark (LO)

Others

Danmarks Erhvervspædagogiske Læreruddannelse Appendix

|

||||||||||||

|

To the top of the page |