|

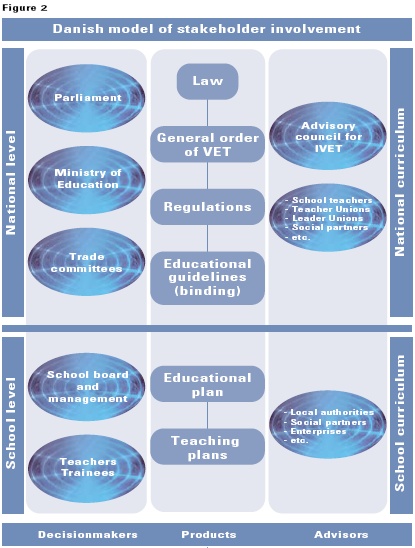

A flexible systemThe Danish VET system is a highly flexible system, offering a wide range of options for the trainees both in terms of time and in terms of contents. It is a system in which the needs and demands of both trainees and enterprises should be fulfilled. The flexibility concerns the framework, the structures, and the contents of VET. Adding to the flexibility of the system is the introduction of assessments of prior learning (APL5) (in Danish: realkompetencevurdering). All trainees have their prior learning assessed before a personal education plan is drawn up. The Danish system is committed to a far-reaching form of flexibility, where individualised learning pathways are drawn up by the trainees, who themselves shape the pace and the content of their own training; a highly flexible, competence-based VET system, where the trainees can take one step of a vocational qualification at a time. Flexible frameworkThe legislative framework for the Danish VET programmes is highly flexible. It is a decentralised system with an overall management principle of management-by-objectives. The overall objectives and framework for VET are drawn up at national level, and the colleges, the enterprises, and the trainees are relatively autonomous within this framework. The framework is flexible in regard to the funding and allocation of resources: the colleges receive taximeter grants per trainee, leaving them with the responsibility of detailed management, budgeting and daily operation; hereby promoting a more demand-led VET system in which the colleges compete on provision and quality. The national curriculum is a framework curriculum, giving vocational colleges, enterprises and trainees the possibility of adapting VET to local and individual needs and demands. The primary objectives and the framework rules must be met, but the specific content of the training may vary from college to college and from trainee to trainee. However, although the framework is flexible, the outcome is fixed: nationally recognised qualifications. The system of management-by-objectives can be divided into four levels, each with its own rules, procedures and instruments for managing-by-objectives: the political level, which has the overall responsibility for drawing up the framework and ensuring the necessary resources, the social partners, which are responsible for developing the VET system and the individual VET programmes, the providers, which are responsible for planning and providing the VET, and the trainee, who is responsible for his/her own training pathway.

Facts about the national legislative framework

In addition to these main acts, all VET programmes are regulated by a specific regulation on the VET programme, stipulating the duration, contents, subject, competence levels, etc. and by a set of guidelines detailing the objectives, duration, structure, subjects, competences, examination requirements, credit transfer, quality assurance, etc. The guidelines were introduced in 2001 in order to simplify the system and to ease the changes in individual VET programmes. These days, the programmes can be continuously adjusted as long as they adhere to the guidelines. This is done on an annual basis, in cooperation between the Ministry of Education and the trade committees. Flexible structuresThe main principle in the Danish VET system is that of dual training, whereby training alternates between education and training in a vocational college and in-company training. This dual training principle is both a pedagogical principle and an organisational-institutional principle, which makes demands on both the pedagogical planning of the programmes and on the cooperation between the colleges and the enterprises. The coordination between school-based and work-based learning constitutes a particular challenge for all the stakeholders in the system, as it is a key factor ensuring coherence in the programmes. Although the dual training principle has been debated animatedly over the past couple of years, it is important to bear in mind that it ensures a smooth transition from training to the labour market. People who have completed a VET programme have an employment rate of approximately 80% one year after completion of their training, which is a strong indicator of a well-functioning system. There are two access routes to the VET programmes: the school pathway and the company pathway. Trainees can either enrol on a basic course or start in an enterprise with which they have a training contract. In both cases, school periods (1/3-1/2 of the entire training programme) will alternate with periods of in-company training (1/2-2/3). The VET system encompasses programmes of durations from 18 months to 5.5 years that are divided into two parts: a basic course, which is broad in its scope and a main course, in which the trainee specialises within a craft or a trade. There are 12 basic courses:

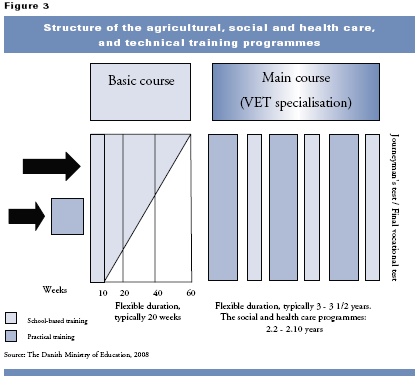

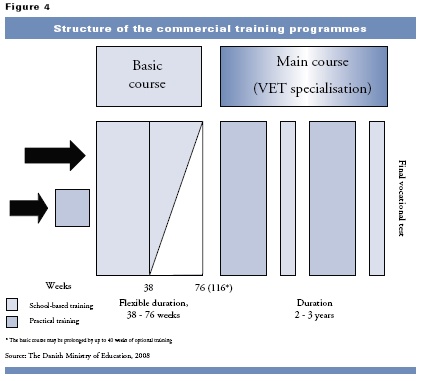

The basic courseIn the agricultural, social and health care, and technical training programmes, the basic course, particularly for the technical training programmes, is highly flexible in terms of both time and contents. The basic course consists of both compulsory and optional subjects. The optional subjects provide the individual trainee with the possibility of acquiring additional qualifications in regard to either the main course or to gain access to further or higher education. The length of the basic course in the technical training programmes will vary from programme to programme, and from one trainee to the next, depending on their qualifications, requirements and needs. The basic courses typically last 20 weeks but may last up to 60 weeks, depending on the proficiency level, requirements and needs of the individual trainee. The basic course of the commercial training programmes is not yet as flexible as that of the other VET programmes. The trainees normally enter via the school pathway and attend a basic course lasting 76 weeks. However, the intention is for the basic course to become more flexible: the introduction of APL, the toning of basic subjects (please see Flexible curriculum, page 33) and the introduction of specialist subjects earlier in the basic course have opened up for increased flexibility, which will constitute a major challenge to the commercial colleges in the coming years. Most trainees enter VET via the basic course and then apply for an apprenticeship once they have completed the course. Everybody who has completed basic schooling can be admitted to the basic course; but a contract with an enterprise is required in order to continue on the main course. The selection of trainees for apprenticeships is carried out on market terms, i.e. the trainee writes an application and goes to a job interview in competition with other trainees. The trainee and the enterprise then enter a binding contract (with a three-month trial period) and the trainee receives wages according to the collective agreement within the sector. During school periods, the enterprise receives compensation from the Employers Reimbursement Scheme (Arbejdsgivernes Elevrefusion AER). This scheme was set up by law in 1977 and is financed by contributions from all employers. Provision of a sufficient number of apprenticeships is of utmost importance to guarantee the trainees within VET an opportunity for practical in-company training and to secure sufficient numbers of qualified skilled workers for companies to employ. Therefore, it is necessary to develop apprenticeship contracts so that they reflect developments within the companies. For example, it is now possible to make an apprenticeship contract for only part of the programme, providing an opportunity for the companies with relatively short term production plans or companies with a specialised production to employ apprentices. If a trainee cannot obtain an apprenticeship, he or she can enrol in school-based practical training. Some 50 VET programmes offer school-based practical training, of which approximately 10 programmes have restricted intake. Through the educational guarantee, the trainees are always guaranteed that they may complete at least one of the programmes within the specific basic course.

The main courseIn the agricultural and technical programmes, the main course normally lasts between 3 and 3 1.2 years, of which the schoolbased part constitutes approximately 40 weeks. The social and health care programmes are shorter: the social and health care helper takes 1.2 years to complete and the social and health care assistant 2.10 years to complete. Most main courses are divided into fixed periods of school-based and work-based training. The aim is to ensure progression in the programmes and coherence between the learning taking place in school and the learning taking place in the enterprise. During the school periods, the trainees meet with other trainees at the same competence level and take part in learning activities at a vocational college. Normally, the periods in school last from one to five weeks. The programme is concluded with either a journeymanfs test or a final project-based examination, in which the trainee is required to show that he or she has acquired the skills necessary to work as a skilled worker within his/her trade. Flexible in time and contentFlexibility in time and content is concretised in the personal education plan and in the flexible curriculum. The personal education planWhen a trainee enters a VET programme, a personal education plan will be drawn up. In the education plan, the trainee is required to describe his/her pathway from unskilled to skilled worker: the objectives, how to achieve the objectives, learning activities, etc. The education plan is drawn up together with a so-called contact teacher (tutor) from a vocational college, and the contact teacher is also responsible for assessing the trainees prior learning and taking the trainees real qualifications into consideration. Thus, every trainee in a VET programme will have drawn up an individual learning pathway. The trainee is actively involved in drawing up the personal education plan and is expected to take responsibility for his/her own learning. The assessment of the trainees prior learning contributes to the principle of lifelong learning, which has been an allencompassing priority in the Danish education system. The assessment is also a way of ensuring coherence between the VET system and the continuing and further education and training system. The VET programmes also aim to provide the trainees with learning skills as well as a foundation for continuous and further education and training. The personal education plan is entered into the national web tool called Elevplan6 (Trainee Plan). Elevplan contains all the trainees personal education plans and electronic logbooks with various papers and notes from the college, etc. A scorecard is drawn up on the basis of the personal education plan, showing the trainees progress towards reaching the overall objectives for the training. The system shows trainees the various learning activities offered by the colleges, and allows them to enrol online. The trainee can also see his/her timetable and absenteeism rate. When the trainee starts training in an enterprise, the enterprise has access to all the relevant parts of the trainees personal education plan and is able to see when the trainee is going back to school, etc. Moreover, the enterprises are expected to enter into a dialogue with the vocational college and the trainee. The aim is for all enterprises to describe the practical training and its objectives in the same way, thus considerably improving the possibilities for coordination between enterprise and college as well as for progression in the training. Flexible curriculumA VET programme consists of four types of subjects: Basic, area, specialist and optional subjects, which are selected and put together by the trade committee. Basic subjects consist of theoretical and practical teaching aimed at providing the trainees with broad vocational knowledge and skills, whilst at the same time contributing to the personal development of the trainees or their understanding of different societal trends. The basic subjects are provided at different levels (F > A). Area subjects are subjects which are common to one or more VET programmes, while specialist subjects are specific to a single VET qualification. Specialist subjects are subjects at the highest level of a VET programme and aim to provide the trainee with specific vocational competency. Finally, there are optional subjects, which are aimed at meeting the interests of the trainees. Up until 2003, the national regulations stipulated that there had to be a specific distribution among the subjects, but now there is more flexibility not only within and across VET programmes, but also from trainee to trainee, depending on the goals which have been laid down in their personal education plan. Footnotes5) Here used as an equivalent to the EU terms of identification, recognition and validation of formal, non-formal and informal learning.6) http://www.elevplan.dk

|

||

|

To the top of the page |