|

|

Capacity Building in Higher Education and Research on a Global Scale

Proceedings of the International Workshop 17 - 18 May 2005 - How can Manpower Needs in Knowledge Based Economies Be Satisfied in a Balanced Way?

Resumé

Here, at the beginning of the 21st century, it has become clear that knowledge is the raw material that will drive development for the foreseeable future. Countries able to control and produce this resource - based to a large degree on higher education and research - will have a clear competitive advantage in the global market. Unfortunately, there is also a dark side: some countries may be left even further behind, further increasing the disparity in the world.

This publication is the result of the international workshop held in Copenhagen 17 - 18 May 2005 entitled “How Can Manpower Needs in Knowledge Based Economies be Satisfied in a Balanced Way?”. The publication discusses how to reduce brain drain, to foster capacity building in higher education and research in the weakest countries, and proposes new strategies for efficient development aid that meet the needs and opportunities of the 21st century.

Content:

I Recommendations

II Perspectives of the International Organizations and of Industry

III Lessons Learned by Donors

IV Lessons Learned by Universities

V Working Groups and Final Plenary Discussion

VI Programme and List of Participants

VII List of abbreviations

Complete table of contents

Colophon

Complete version of the publication in HTML (345 kB)

Complete PDF-version of the publication (2.748 kB)

Undervisningsministeriet

Frederiksholms Kanal 21

1220 København K

Telefon 3392 5000

Table of Contents

Workshop Scope

Foreword by Torben Krogh

Foreword by the Programme Committee

Opening Address by Jens Jørgen Gaardhøje

Opening Address by Henrik Toft Jensen

I Recommendations

Capacity Building in Higher Education and Research: A Key Component of Efficient Global Development

II Perspectives of the International Organizations and of Industry

Developing Countries and the Global Knowledge Economy:

Opportunities and Responsibilities of High Tech Industries

Consequences of Current Trends in S&T Higher Education

The Role of International Organizations in Handling Brain Drain

III Lessons Learned by Donors

Swedish Experiences of University Support and National Research Development in Developing Countries

Donor Experiences from Capacity Building Proposals Related to Knowledge Society Construction

International Academic Exchange between Capacity Building and Brain Drain – the Case of the German Academic Exchange Service

IV Lessons Learned by Universities

Lessons from Building a Research Network (SUDESCA) in Central America

The Experience from an ENRECA Capacity Building Project

Globalisation of Tertiary Education and Research in Developing Countries – The Malaysian-Danish Experience

Capacity Building for Higher Education in Developing Countries – A Part of the Western World University Portfolio?

V Working Groups and Final Plenary Discussion

Working Group 1

Working Group 2

Working Group 3

Reporting from the Closing Session: Can We Do Better within Higher Education and Research?

VI Programme and List of Participants

Workshop Programme

List of Participants

VII List of abbreviations

List of abbreviations

Workshop Scope

Economic growth is increasingly tied to the supply of individuals with advanced research based education in science and technology (S&T). Countries that possess such resources will be able to attract research and development (R&D) activities of international companies and are likely to see a marked growth of new, domestic high technology industries.

However, many rich countries are unable to convince a sufficient number of their brightest young people to study the science and engineering subjects in high demand. This has led to an increasing import of young scientists from poor countries (brain drain). Most of these countries cannot afford the loss of their best talents and of the investments in their education.

The workshop aims at clarifying the problems related to capacity building at a high level in S&T in industrialized and developing countries and to explore solutions that ensure a balanced and ethically correct supply of this highly valuable “soft” resource. These solutions involve national initiatives in rich and poor countries, aid and development programs targeting capacity building in advanced S&T and the need for broader international cooperation and coordination.

The workshop is organized by the Science Committee of the Danish National Commission for UNESCO and the Niels Bohr Institute and is sponsored by the Danish Ministry of Education, the Niels Bohr Institute/University of Copenhagen and the University of Aalborg, Denmark.

Foreword

by Torben Krogh, Chairman of the Danish National Commission for UNESCO

Through at least three – perhaps four – decades the traditional European and North American donor communities have given low priority to higher education in their foreign aid. The perception has been that such education is restricted to a rather limited and comparatively wealthy segment of the developing societies. Furthermore, one of the first main theories of foreign aid – the so-called trickle down effect – turned out to have major flaws when it came to the practical consequences.

Experience in recent years has shown, however, that higher education does play a vital role in the overall development of societies with a modest gross national product per capita. During the Workshop at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen 17 – 18 May 2005 – the result of which is published in this report – several examples were highlighted in this context. Also, the participants, contributing from very different professional backgrounds, presented very convincing arguments of a more analytical nature to underscore the point, that higher education should be given higher priority in the development cooperation.

Some donor agencies and countries – notably Germany and Sweden – have moved in that direction in recent years. Nevertheless, as it becomes clear from the proceedings much still has to be done. At the same time it is clear that such a process will not be without complexities. One serious threat, hovering over such an effort, will be the risk of brain drain. During the later years highly developed countries have suffered from lack of qualified, highly educated persons. To various degrees they have tried to make good for this by attracting such individuals from the developing world.

Here it has to be realized, however, that this phenomenon is closely related to lack of research possibilities, professional challenges and proper salaries in the countries of origin. Consequently, brain drain can not be countered just by a change of policy in the receiving countries. The most important factor in this regard is reinforcement of the scientific and research activities in the developing countries themselves.

This point is forcefully underscored by the plurality of presentations in the proceedings. For us in the Danish National Commission for UNESCO it has been rewarding and eye-opening to be associated with this initiative. It is with great pleasure that I recommend this publication to everyone who is engaged in international development cooperation and more specifically in the thrust to strengthen the educational component in foreign aid – not least higher and research based education.

Foreword

by the Programme Committee

Universities in many industrialised countries have a dilemma regarding developing countries. On the one hand faculty and students may be highly motivated to deal with exactly their problems in terms of education and research, and often the universities in their policies and strategic goals express solidarity with the South (the developing countries). On the other hand, the ministry under which the universities operate usually has no policy regarding development in general (not to speak of development in foreign countries), and there is no budget to sustain possible ambitions of this kind. Governments often have a strong interest in developing countries. For example, during times of overheated economies, governments may try to find badly needed talent by offering scholarships to top level foreign students or lucrative jobs to skilled graduates from abroad. This leads to a debate about brain gain by wealthy countries at the cost of brain drain in developing countries.

On this background the Workshop Programme Committee consisting of representatives from Aalborg University, University of Copenhagen and Roskilde University decided to organise a workshop to analyse the problems and seek ways and means of addressing the dilemma constructively. The workshop was sponsored jointly by the Danish National Commission for UNESCO, University of Copenhagen and Aalborg University.

The Programme Committee is grateful to speakers, sponsors and participants for making the workshop possible and thereby also this publication of the results from presentations and discussions. Special gratitude goes to the authors who took the time to write down their oral presentations and to the rapporteurs who took notes during discussions. The rapporteurs were Ingrid Karlsson from Uppsala University, Ole Mertz from Copenhagen University,and Laura Zurita, Birgitte Gregersen and Eskild Holm Nielsen from Aalborg University. We thank Helle Glen Petersen from the secretariat of the Danish National Commission for UNESCO who did an excellent job in pulling strings together before and after the workshop and getting this publication ready for print.

The Programme Committee has tried to summarise the outcomes of the workshop and their own views in the introductory paper, and to make some conclusions. However, the reader is encouraged to consult the original papers provided by the authors in full in this booklet. We hope that this publication will provide food for thought regarding capacity building in higher education and research in general, and the role universities may play in bilateral and multilateral international aid programmes in particular.

Opening Address

by Jens Jørgen Gaardhøje, Professor, the Danish National

Commission for UNESCO and the Niels Bohr Institute

Distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen.

It is my significant pleasure to welcome you in Copenhagen for the work-shop:

Capacity Building in Higher Education and Research on a Global Scale

organized by the Danish National Commission for UNESCO. The meeting has been sponsored by the Danish Ministry of Education, The University of Aalborg and the Niels Bohr Institute/University of Copenhagen.

There is a worldwide perception that continued economic growth in the world will increasingly be based on a new type of “raw material”. This new resource cannot be dug out of the ground like gold and diamonds, but is tied to the ingenuity of humans. Indeed, in an increasingly complex world, development is intimately tied to creating new materials, methods, and products. The country that has the best conditions for creating new ideas and concepts also has the most direct route to gaining an edge in world competition to the benefit of its population.

Needless to say this requires individuals with advanced training and higher education and, in particular, with research training, principally within Science and Technology.

However, the “raw material” of the “knowledge based economy” is hard to come by and most countries experience a shortage of people with advanced training in research and development.

The threshold is low for trying to compensate for own shortcomings by “borrowing” from others by providing conditions of living and research that far exceed those that are available in the country of origin. This leads to the well know brain drain problem for some, to a brain gain for others.

The brain gain dilemma is complex and has many overtones related to economic development. Unchecked brain drain increases the divide between rich and poor countries by draining poorer countries of their costly investment and hinders the development of many regions of the world. At the same time brain gain is for other countries a condition for maintaining a high standard of living.

Brain drain is thus a global problem which can only be overcome by building up sufficient capacities in the countries and regions. How to do that in a balanced way is the subject of the present workshop. I hope that our discussions in the next two days can help clarify the problems and issues at hand and perhaps also provide some guidelines for how to act in the future.

I hope that the participants will be inspired buy the atmosphere of this venerable institute founded by Niels Bohr.

Bohr as you know, a passionate believer in the open world and the free exchange of ideas, founded an institute based on international cooperation, running an extended visitor program here at Blegdamsvej, most of whom returned to their home countries and build up new areas of science, often founding what we today would call centers of excellence.

I invite you in the break to take a look at the pictures framing this room.

I trust that our discussion will be equally far reaching and lively as the many that have taken place and still take place here on physics and quantum mechanics, and …. that they will make up for the hard benches that have changed little since the 20’ties.

On behalf of the organizers, Erik W. Thulstrup, Jens Aage Hansen and myself, I wish you all a good and productive workshop.

Opening Address

by Henrik Toft Jensen, President, Roskilde University,

Danish Rectors’ Conference

It is a pleasure for me to address this workshop “Capacity Building in Higher Education and Research on a Global Scale”.

In a fast developing world it is important to be aware of and to create actions to meet manpower needs in Science and Technology.

First of all it is universities and scientists who should be active in this field and as the chair of the International Committee of the Danish Rectors’ Conference I can inform you that Danish universities have a current project on building universities for the future. This is in response to internal demands for being live and active academic institutions working on the leading edge in research and higher education. And it is in response to external demands from government, civil society and industry regarding partnerships in developing a knowledge society, e.g. in terms of advanced development and use of science, technology and innovation.

Actions from international organisations are very important, and I would like to stress that capacity building and North-South relationship is on the agenda in the two global university organisations “International Association of Universities” and “International Association of University Presidents” as well as in many regional university organisations such as the European University Association.

I would like to stress that global organisations are very important in this capacity building. Therefore, it is promising that representatives from The World Bank, OECD and UNESCO are participating in this conference and the workshops. This will contribute to secure the global dimension.

But let me return to researchers and universities active in this capacity building.

International and mutual interactions as well as establishment of partnerships across traditional borderlines (cultural, academic, geographical, and technical) are necessary for universities to meet future and global demands. There is a long tradition for doing so, in particular between universities in the industrialised world. Interaction between countries and universities in the industrialised and in the developing world is much less obvious and not always mutually beneficial and productive. But over the past decade there are some interesting examples of Danish university involvement in capacity building in the 3rd world.

One example is the ENRECA (Enhancing Research Capacity in Developing Countries) with a budget of app. US $ 8 million/y and about 40 projects running a project contributing to capacity building and partnership between North and South. The ENRECA evaluation in 2000 also identifies a dilemma between doing research and building capacity to do research and use the results. The weaker the economy, the more need for capacity building before real research can be done. Occasionally, this places the donor country researcher in a difficult position, because the demand at home is publishable results from real research, while time spent on education and tutoring does not create academic merit. But institutional and educational capacity building is a prerequisite for research, and therefore we hope that the donor agency DANIDA (Danish International Development Agency) will increase budgets to allow for a combined building of institutional, educational and research capacity. Danish faculty and graduate students have performed very well and with great enthusiasm in ENRECA projects and overall the evaluation in 2000 was very positive. Universities have contributed financially in terms of time and use of equipment.

Another example is Danish University Consortia for Environment and Development, DUCED-I&UA for Industry and Urban Areas, and DUCED-SLUSE for Sustainable Land Use and Natural Resource Development. These two consortia comprise some 20 universities in Botswana, South Africa, Thailand, Malaysia and Denmark and the annual budget from the donor (DANIDA) was app. 4 million US $/y. Universities contributed a similar amount of resources.

The DUCED programme was designed for education capacity building (curricula), but in order to install new capacity at universities and maintain the enthusiasm of faculty and graduate students, the research component increased over time in terms of several Phd. students enrolled and forming a core group of capacity builders.

What can been learnt from the ENRECA and DUCED programmes is very important.

The programmes have been successful in building capacity, in particular when combining institutional, educational and research aspects in the programmes.

The programmes have been very cost effective, but obviously the institutional and educational capacity building process in recipient countries requires extra input from donor agencies. The Danish universities cannot absorb this in their budgets which are made for national activities so far.

The experience gained by Danish universities is of high value for both Danish students and faculty in terms of preparing for careers in Denmark and internationally. So in effect, capacity building has taken place both in South and North and has been mutually beneficial.

The simple conclusion is that Danish universities are ready for more of that type of experience and international networking, simply because it means providing the foundation for knowledge societies, and the basis for global prosperity, democratic development, and reduction of poverty.

This workshop addresses capacity building in higher education and research and there is focus on the potential conflicts of interest between the rich and the poor countries. Universities in both worlds provide the ideal platform for an important continued dialogue, oriented at creating action towards mutually beneficial progress. A dialogue orientated at creating of a mutually beneficial roadmap and define action to achieve progress. The workshop also includes donor institutions and university representatives from different countries. The ground seems to be laid for a constructive exchange of experience and for shaping some of the foundation necessary to move ahead.

On behalf of the Danish Rectors’ Conference I look forward to the results from this workshop. I hope mechanisms for increased future university involvement in capacity building and for better interaction between universities and donor organisations will be some of the results of your efforts.

I wish you two successful days in Copenhagen.

I Recommendations

Capacity Building in Higher Education and Research: A Key Component of Efficient Global Development

by the editors: Erik W. Thulstrup, Jens Aage Hansen

and Jens Jørgen Gaardhøje

Abstract

This paper discusses development through capacity building in higher education and research (CBHER), especially how to achieve this in the context of the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDG). It is argued that investment in CBHER may be a direct and efficient route to economic development. Based on the presentations and discussions during the Workshop at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, May 17-18, 2005, nine conclusions are developed and presented in this introduction to the Workshop Proceedings by the Programme Committee.

Paradoxes in development and globalisation

It is becoming increasingly clear that the fast growth of three groups of people will dominate international relations during the coming decades. The three groups are:

- The fast growing group of old, relatively wealthy people in Western countries and Japan

- The group of increasingly wealthy and productive younger people in successful developing countries like China and India, and

- The group of young people in high-birth-rate and low economy countries, who are only given few (educational) opportunities for a better life and are increasingly dissatisfied and bitter; this unfortunate situation is a significant part of the root system of terrorism.

At the same time, the group of desperately poor, for example in Africa, is not likely to be reduced fast enough. Globalisation, that has been so useful for China and India, does not seem to help Africa nearly as much.

Thirty years ago South Korea and Singapore were poorer than many African countries, but through a major educational effort that made it possible for them to use up-to-date technologies efficiently, they were able to create fast economic development and have long ago managed to drastically reduce or eliminate poverty. Surprisingly, their successful strategies were not copied much by other developing countries or donors, at least not until China and India started doing so on their own. But the recent success of these huge countries is hard to overlook. Other large developing countries, like Pakistan and Brazil, are trying to follow similar strategies and there are indications that also these countries may be successful, even without much help in the form of foreign aid.

Economists have for years tried to demonstrate a clear relationship between development aid and actual economic development. However, it seems hard to find an obvious correlation between the two (see, for example, R. Rajan in the Dec. 2005 issue of Finance and Development). In the case of Danish aid, the correlation may at times seem negative. Many of the countries, for example in Africa, that receive Danish aid have experienced a striking lack of efficient development, while countries, that many years ago stopped receiving Danish aid, including China and India, recently have been much more successful in creating economic development and reducing poverty. Would Denmark be able to help poor countries in Africa by getting out of the aid business? Several economists would agree, but there may be a better way.

Building capacity in higher education and research

What are the main differences between the traditional aid driven development strategies, for example those supported by Denmark, and the obviously successful ones used by China? One striking difference is that the former tries to make up for the uneven and unfair division of wealth in many developing countries by attempting to support the poorest part of the populations in these countries directly. The latter gives high priority to the creation of wealth, with less initial emphasis on how it is divided. However, experience, e.g. from Singapore and Korea, shows that the poorest part of the population also may benefit significantly from this strategy, while attempts to divide existing wealth more fairly have led to disasters in Sri Lanka.

Another striking difference is the emphasis placed on higher education, especially within science and technology, in the successful developing countries, from Singapore to China. In contrast, the traditional donor guided development strategy puts emphasis on basic (primary) education. While there is no doubt about the usefulness of good primary education, it is not enough to support economic development. Both China and India are these years demonstrating that clever use of research based modern technologies has been able to create economic development much more efficiently, as it was shown earlier by Singapore and South Korea. These successes have been noticed in South Asia: India has started a billion dollar project with the purpose of strengthening engineering education at the ”second level” of higher education institutions, Pakistan has increased funding for university research in Science and Technology by eight thousand per cent(!), and Bangladesh is negotiating a large World Bank loan for S&T university research.

The by far largest development aid project these years is the Chinese development efforts in the backwards, Western part of the country. Not surprisingly, the highly successful and wealthy universities in the rich Eastern China are among the main players in these efforts. In the Danish aid philosophy, higher education is still often considered a luxury – it is felt that the educational needs of developing countries are limited to primary education and vocational training. This seems still to be the case, even after the development banks have started to recognize the key role of higher education for economic development. However, discouraging developing countries from gaining access to knowledge at highest levels, for example high technology knowledge may result in a new form of colonialism and this is hardly what Denmark wants!

Higher education is not only useful for the economic development. It may also have a significant political impact by creating cadres of informed and thinking young people in support of democratic reforms. There is little doubt that politics is important, and there is some indication that democratic systems on the whole are more efficient in reducing human suffering than other political systems. Western donors like Denmark have for years tried to strengthen democratic and peaceful developments in developing countries by directly supporting democratization efforts, but often with mixed results. However, many examples show that if young people are given useful higher education at an international level, they will be both able to and motivated for supporting democratisation efficiently, and will be much less tempted, for example, to join terrorist groups.

The civil war in Sri Lanka, that has now lasted over twenty years, was to a large extend triggered by an unfair system for access to higher education. Many young people found a life as fighter or even terrorist more attractive than the only alternative that was available without higher education, a life as a poor farmer. This was recognized many years ago in Sri Lanka, and university enrolments were expanded drastically. However, most of the new educational opportunities were in low-cost subjects that did not lead to employment, especially in the humanities. The country now has to struggle, not only with a civil war, but also with almost 30,000 unemployed and unemployable university graduates (while there still is a shortage of engineers in the country). This has not created political stability or economic development.

Using the capacity

It is not enough to establish capacity, it must also be used. In order to create development, higher education and research must be useful for society and lead to good employment opportunities for the graduates. The universities must be part of the surrounding society and not isolated ivory towers. Too often, donor or development bank funded university projects have attempted to strengthen the academic standards at universities in developing countries, with little regard to the impact on society, as illustrated in Fig. 1

Figure 1. Society and the ivory tower (university) before (left) and after (right) a traditional, donor funded university capacity building project. Clearly, the situation in real life has not changed much (Kornhauser and Kos, 1992, by permission).

Today ”knowledge sharing” is becoming a key phrase – those who have useful knowledge (e.g. good universities) must share it with those who need it (e.g. industry, the public sector, or the public in general, see Box 1). This is not easy: many developing country universities are completely unprepared for such demands, and even local knowledge users, for example industry, are frequently very hesitant to let students invade their facilities. Fortunately, those that have accepted it are usually very satisfied with the performance of the students.

Box 1. Beauty without Pain in Nairobi

| In the mid-1980s the Chemistry Department at the University of Nairobi, Kenya, started encouraging groups of undergraduate students to carry out their research projects on real life problems. One group analyzed the heavy metal content of eye liners in the local market; especially women of Indian origin used these in large quantities. The students found that the amounts of heavy metals in some of the products were extremely high, and actual health problems could be attributed to these. Other eye liners in the market were completely safe, at least with respect to heavy metals. This would have been just another research project if the local media had not noticed the results. The risks related to the heavy metal content became front-page news in the newspapers in Nairobi and this publicity helped save many women from unpleasant injuries. |

Most Danish universities have overcome such knowledge sharing problems and work successfully with industry and other knowledge users. The important integration of education, research, and real life applications has actually been accomplished at modern Danish higher education institutions, e.g. at the universities at Aalborg and Roskilde where problem based learning is practiced at all levels. Using academic capacity in practice is a key competence, which many developing country universities still lack. If they could obtain such skills, development might benefit immensely.

Figure 2. Integration of education, research and real life applications as it is practiced at modern Danish universities. Many developing country universities have not yet accomplished such integration, although it is essential for knowledge sharing.

Workshop observations on the development process

The workshop looked at capacity building in higher education and research for fair global development from different stakeholder positions, e.g. international institutions, industry, donor agencies and universities, representing both donor and recipient countries. In order to put the entire workshop outcome in context, the main points of each speaker are here summarised briefly. This allows for the attempt to conclude the results of the two day exercise at the end of this article. While neither workshop nor discussions were focused on the Danish situation in terms of aid policy or university involvement, Denmark did serve as benchmark in the discussions during the workshop and is used as such in the conclusions.

Industrial viewpoints are expressed by Lene Lange from Novozymes. Growth economies such as in China, India and Brazil were mentioned as attractive to high tech industries due to growing markets, educated labour and good infrastructure. Win-win situations are likely to occur without intervention from international aid agencies. In poor developing countries there is less immediate interest in investment from the high tech industry, which means that there is an urgent need for aid agencies to target action on capacity building and technology transfer. Training of young talents abroad is not necessarily brain drain, but may also be a way of long term capacity building, because many trained individuals return with important, international academic and industrial links. Clean production in for example the agro-industrial sector is but one example of interesting drivers in developing countries that could also attract also foreign industrial investment for win-win projects.

By a virtual analysis of the university of the future and acknowledging the growing need for knowledge, Jamil Salmi from World Bank challenges both industrialised and developing countries to handle a number of daunting, but crucial tasks. These include expanding the capacity for tertiary education, reducing inequality of access, improving quality and relevance of education, and installing more effective governance and management systems. Establishing partnerships with and use of experiences from foreign universities that are leading within learning strategies is one way of reforming tertiary educational sectors. Quality control based on evaluation of graduate competency is another, and flexibility in adaptation to new needs of the country a third.

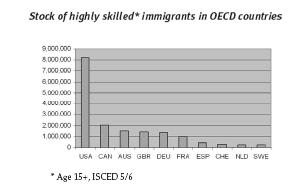

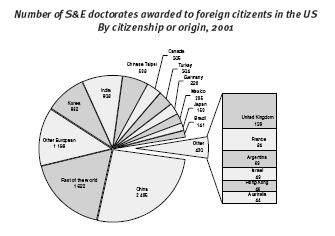

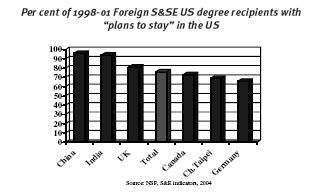

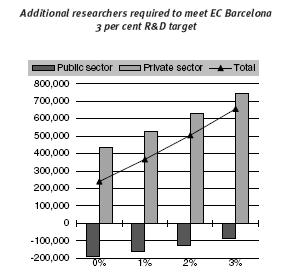

Michael Oborne from the OECD focuses on highly skilled immigrants in OECD countries. There is a clear tendency for several of these countries to attract, educate and keep talent within their borders. But changing conditions make it possible for talent to be trained at high quality universities in for example China and India. Multi-national companies are other active agents of change in that they transfer knowledge and “skilled human capital” across borders according to markets and opportunities. Common to all countries that want to improve development and create a better living for their citizens are that they must create a knowledge based economy, i.e. make long term investment in human capital.

Julia Hassler from UNESCO discusses the mobility of highly skilled manpower, including phenomena such as brain gain, -drain, -return, -exchange, -wastage, etc. She suggests the consideration of brain circulation with potential benefits to all countries involved. International organisations should play a positive role by assisting the mobility of workers in science and technology and maximise benefits. The “diaspora” concept (expatriate skilled capital considered an asset to the home country) together with efficient networking may be an attractive new development tool. She points out that members of the UN family must include in their millennium goals for every country the development of human resources to the highest level. International organisations should be prime movers in the process of connecting educators in a global network to reach the final Millennium Development Goal, i.e. “Global Partnership for Development”.

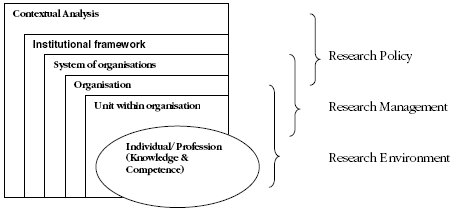

Tomas Kjällqvist from the Swedish International Development Agency provides evidence of the effect of Swedish support to developing countries through a strengthening of their research capacity, specifically at the institutional level. It happens on the background of a rediscovery among international donors of the significant role of science and technology for development. Cooperation between Swedish and foreign universities has strengthened both local research environments and international scientific information exchange. The aspect of coupling education and research was one reason to concentrate Swedish aid to universities rather than other research institutions. Strengthening of national research policies will be a target for Swedish capacity building programmes, and donor coordination in this field is seen as important.

Assisting the mobility of some 50,000 academics (students, faculty and other scientists) each year is one of the results of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) as described by Michael Harms. It is a two-way programme, but the emphasis is on incoming academics (to Germany). The independence of DAAD from the donor community is interesting in terms of programme design and development of new instruments in capacity building within higher education, e.g. demand driven courses and research projects, bottom-up institutional capacity building, and alumni institutions for continuity beyond project periods. The return to the home country of skilled human capital is considerable.

Leiner Vargas describes the Sustainable Development Strategies for Central America (SUDESCA), a project financed by DANIDA (Danish International Development Agency) as part of the ENRECA (Enhancement of Research Capacity in Developing Countries) Programme during the period 1996-2006. He emphasises the change from at first research only to a more balanced process involving both education and research. Learning by doing in interaction with local companies is an essential element of success in project implementation. One of the conclusions by Vargas is that university capacity building should concentrate on issues where society can benefit, not only economically but also in terms of general acceptability. The duration of capacity building programmes is crucial for their success. Trust takes time to build from scratch and long term financing must be available for capacity building (CB) projects to succeed.

P. Agamuthu describes Globalisation of Tertiary Education and Research in Developing Countries based on experiences from the DANCED/DANIDA funded capacity building project involving Malaysian and Danish universities. The project focused on industry and urban areas and lasted from 1998-2004. Malaysia belongs to the group of growth economy countries and this may partially explain that the participating Malaysian universities in only 3 years were able to change learning paradigms, acquire new EU funded projects in curriculum development, and establish numerous linkages for career development and scientific collaboration. Agamuthu stresses the mutual recognition of cultural and socio-economic differences as positive and mutually beneficial opportunities for both South and North, i.e. the exchange must be two ways and funding must somehow be matched to achieve this balance in the longer run.

Henrik Secher Marcussen reports on experiences from an ENRECA project in Burkina Faso, 1994-2006. He reviews the project in regard to the initial targets set, but also in a wider context of development in a globalising world. This leads to some key questions and observations that are relevant to capacity building (CB) projects like ENRECA and to aid programmes in general. 1) National rather than donor priorities should determine topic and scope of CB projects. 2) Aid programmes aiming directly at poverty reduction would usually not offer the right context for good national CB programmes; high quality and technologically advanced research and tertiary education may have to be targeted separately. 3) The donor country may have to involve both its aid agency and its ministry for science, technology and innovation when planning and negotiating CB programmes for priority countries.

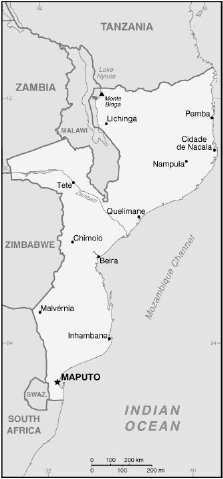

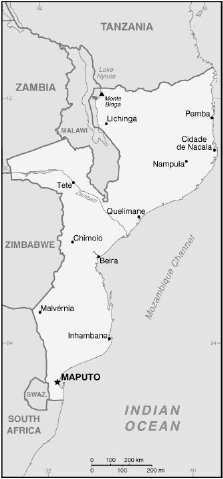

Stig Enemark reports on the planning of a recent CB project from Mozambique. The project is not likely to become funded and implemented due to lack of mutual understanding and coordination between the key stakeholders. It is argued that capacity building in higher education and research should be part of university strategy portfolios and be supported by relevant stakeholders such as donor agencies, ministries, trade and industry. It is important that such capacity building activities be seen as mutually beneficial, i.e. not only as key drivers for societal development in the recipient countries, but also as necessary for building relevant international capacity and institutional innovation in donor countries.

Conclusions

Base on the presentations and discussions during the workshop the following may be concluded:

- CBHER should more specifically enter the MDG

- CBHER is a prerequisite for skilled human capital and economic development

- Investment in CBHER should preferentially be separated from other aid issues, at least initially

- The poorer the economy, the longer support for CBHER is required

- Stakeholder commitments and facilitating infrastructures are vital for CBHER

- Capacity building must also target concrete societal needs

- International partnerships at the university level improve global trust and fair trade

- Mobility and staff exchanges are needed to enhance CBHER and create mutually beneficial brain gains

- Efficient CBHER at universities in the South often requires a new-mind set and creative actions by stakeholders in the North, including governments.

The UN Millennium Development Goal (MDG) number 8 prescribes “global partnership for development”. The workshop provides ample evidence that this requires more specific mention of capacity building in higher education and research. While “universal primary education” has its own MDG number (2), it has to be recognised that higher education and research has become a basic need, not only in industrialised countries. Also in developing countries a considerable effort is requited, if they want to participate in the new global economy.

Several examples presented by speakers and participants showed that economic growth is necessary for development to take place, and that higher education (skilled human capital) and research are key factors for any country to realise economic development.

Investments in higher education and research serve a long-term development goal. Thus it may have to be initially separated from other concerns in order not to confuse matters, e.g. by not asking for poverty reduction as an immediate outcome, although it is on the top of the list and absorbs the majority of donor concerns.

Growth economies are different from developing country (stagnation) economies and the ways to implement capacity building in higher education and research will have to differ accordingly. The poorer the economy, the longer the process may have to last. A staggered approach will possibly benefit both donor and recipient country. Important ingredients in the process are mutual trust building between partners (e.g. universities) in South and North, as well as agreed quality assurance measures (e.g. the use of output and competency building rather than input as key parameters).

Stakeholder co-ordination and facilitating infrastructures are necessary in both recipient and donor countries for CBHER projects to succeed. Stakeholders are, for example, government, industry, trade, and universities.

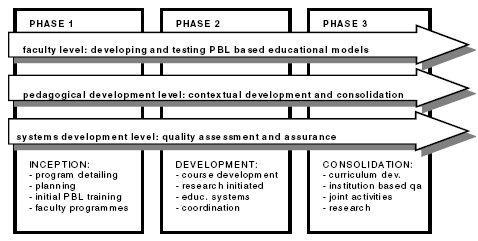

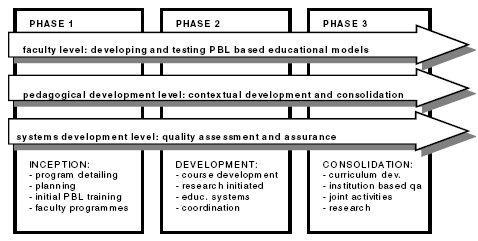

University capacity building should also target concrete societal needs especially by making them part of problem based learning (Fig. 2). This is beneficial for all parties involved, from the students in the learning process to the problem provider who will benefit from new information and understanding of the problem and may even find new innovative solutions.

International partnerships between donors and developing countries at the university level help create mutual trust and prepare for future trade relations. Understanding between new generations of leaders, democratic development, and fair deals between friendly partners rather than edgy and alienated competitors may be some of the outcomes of cooperation at this level.

Mobility and scholarships are vital instruments in capacity building in higher education and research. Sweden and Germany offer role models in this connection worthy of further analysis and possible use in other countries. One of the interesting observations from the presentations at the workshop is that increased mobility reduces the brain drain problem, because in a long term perspective there will be sharing of knowledge and skilled human capital. Mobility is given high priority in a variety of programmes within the EU, but only for the 25 member states. A comprehensive programme for mobility between the EU countries and the rest of he world, especially the developing world, is missing. It might be possible for North European countries to create a basis and a model for increased mobility between North and South. Among other, the alumni model of the German DAAD programme may deserve further analysis in terms of mechanisms, costs and development impact.

Capacity building at universities in the South through partnerships must be part of the development strategies of universities in the North, if researchers and educators are to become fully engaged. Support from ministries, other agencies and private stakeholders in the donor country will be necessary, but is essentially absent in many countries. This is, for example, the case in Denmark, in contrast to the official Danish government strategy for participation in global economic development (published April 2006 under the title “Progress, Innovation and Social Security”). There is a need for an improved understanding of the new global situation, and priorities must be accordingly revised, if aid programmes are to produce a long-term increase of human capital in developing countries as the backbone of sustainable economic development.

II Perspectives of the International Organizations and of Industry

Developing Countries and the Global Knowledge Economy:

New Challenges for Tertiary Education

by Jamil Salmi, Coordinator of the World Bank’s network

of tertiary education professionals

Abstract

Developing countries face significant new challenges in the global environment, affecting not only the shape and mode of operation but also the purpose of their tertiary education system. Among the most critical dimensions of change are the convergent impacts of globalization, the increasing importance of knowledge as a main driver of growth, and the information and communication revolution.

Both opportunities and threats are arising out of these new challenges. On the positive side, the role of tertiary education in the construction of knowledge economies and democratic societies is now more influential than ever. Tertiary education is central to the creation of the intellectual capacity on which knowledge production and utilization depend and to the promotion of lifelong learning practices. Another favorable development is the emergence of new types of tertiary institutions and new forms of competition, inducing traditional institutions to change their modes of operation and delivery and take advantage of opportunities offered by the new information and communication technologies. But this technological transformation carries also the danger of a growing digital divide among and within nations.

At the same time, most developing and transition countries continue to wrestle with difficulties produced by inadequate responses to long standing challenges faced by their tertiary education system. Among these unresolved challenges are the sustainable expansion of tertiary education coverage, the reduction of inequalities of access and outcomes, the improvement of educational quality and relevance, and the introduction of more effective governance structures and management practices.

In this context, the presentation will focus on the role of tertiary education in building up the capacity of developing countries to participate in the global knowledge economy client countries.

Coordinator of the World Bank’s Tertiary Education Thematic Group. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, the members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent.

Introduction

Welcome to the university of the future. All visitors will be greeted by a robot receptionist. Incoming students will receive a free ipod, a Blackberry, a laptop and a bicycle. Students in need of financial aid will compete for scholarships auctioned online on Ebay. In the university of the future, each student will have an individualized program to suit his / her specific career plans or study interests. Courses will be systematically redesigned every two years. The validity of degrees will be only five years. Most students will enroll at the same time in at least two or three tertiary education institutions to get credits towards their degree. Most courses will be online, through dynamic interaction with web-based cognitive tutors based on artificial intelligence. In the university of the future, there will be no physical library or laboratories, only e-libraries and i-labs. Daily communications from the university administration will be transmitted through SMS sent directly to the students’ cellular phones. Students who graduate on time will get a $500 cash reward, whereas graduates who don’t find a suitable job within six months of graduating will be reimbursed the full cost of their studies. To stimulate institutional responsiveness and relevance, the university president will tax each department at the beginning of the academic period and award the most innovative department a one million dollar prize at the end of the period. Professors will receive a bonus based on the labor market outcomes of their students. Overall, the university will receive only 10 per cent of its income from the government. The most sought after program will not be the MBA anymore, but the Master in Fine Arts recognized for creativity skills imparted to future industry leaders.

While this description of the university of the future may seem like an improbable science fiction dream to some, or a terrifying nightmare to others, each element mentioned above can actually be found in some form among today’s universities. These futuristic features are symbolic of the rapid transformation affecting tertiary education in the industrial world. In the past few years, many countries have witnessed significant transformations and reforms in their tertiary education systems, including the emergence of new types of institutions, changes in patterns of financing and governance, the establishment of evaluation and accreditation mechanisms, curriculum reforms, and technological innovations.

But the tertiary education landscape is not changing at this impressive speed everywhere. Most developing countries continue to wrestle with difficulties produced by inadequate responses to long standing challenges. Among these unresolved challenges are the sustainable expansion of tertiary education coverage, the reduction of inequalities of access and outcomes, the improvement of educational quality and relevance, and the introduction of more effective governance structures and management practices.

And yet, having strong and dynamic tertiary education institutions has never been as essential for developing countries faced with the need to accelerate economic growth and reduce poverty. In this context, the paper focuses on the capacity building role of tertiary education. It starts by recognizing the importance of knowledge for developing countries in the pursuit of better economic and social outcomes. It then outlines the changing education and training needs arising from increased reliance on knowledge. The third section describes the rapidly evolving tertiary education landscape. In the final section, the paper examines the opportunities and challenges brought about by these new developments.

Growing importance of knowledge for developing countries

Economic development is increasingly linked to a nation's ability to acquire and apply technical and socio-economic knowledge, and the process of globalization is accelerating this trend. Comparative advantages come less and less from abundant natural resources or cheaper labor, and more and more from technical innovations and the competitive use of knowledge. Today, economic growth is as much a process of knowledge accumulation as of capital accumulation. It is estimated, for instance, that firms devote one-third of their investment to knowledge-based intangibles such as training, research and development, patents, licensing, design and marketing. In this context, economies of scope, derived from the ability to design and offer different products and services with the same technology, are becoming a powerful factor of expansion. In high-technology industries like electronics and telecommunications, economies of scope can be more of a driving force than traditional economies of scale.1

At the same time, there is a rapid acceleration in the rhythm of creation and dissemination of knowledge, which means that the life span of technologies and products gets progressively shorter and that obsolescence comes more quickly. In chemistry, for instance, there were 360,000 known substances in 1978.

This number had doubled by 1988. By 1998, there were three times as many known substances (1,700,000). Almost 150,000 new “patent equivalents” are added to the Chemical Abstracts data base every year, compared to less than 10,000 a year in the late 1960s.

In addition to stimulating economic growth through increased productivity resulting from innovation, knowledge contributes to poverty reduction and facilitates the achievement of most of the Millennium Development Goals.

“Science, technology and innovation underpin every [Millennium Development] goal. It is impossible to think of making gains in concerns to health and environment without a focused Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) policy, yet it is equally true that a well-articulated STI policy can make huge gains in education, gender equality or upgrading of living conditions.”

(UN Science, Technology and Innovation MDG Task Force Interim Report, December 2003)

Drastic progress in agricultural output, for example, comes from the application of the Green Revolution. Similarly, remarkable advances in the resolution of health issues are owed to the application of scientific knowledge and the work of highly qualified health personnel. Simple GPS handheld devices can now be used easily to find water in drought stricken areas. All countries also need the scientific capacity to understand critical issues such as global warming, the pros and cons of using genetically modified crops, or the ethical dimensions of cloning. Finally, progress in seismology, vulcanology and climatology has enhanced the ability to anticipate and prepare for natural disasters like floods, tsunamis and droughts. The existence of a tsunami warning system around the Indian Ocean, similar to the one already in place around the Pacific Rim, would undoubtedly have saved thousands of lives on December 26, 2004.

A direct product of the application of science and technology is the information and communication revolution. The advent of printing in the 15th century brought about the first radical transformation in the way knowledge is kept and shared by people. Today, technological innovations are revolutionizing again the capacity to store, transmit, access and use information. Rapid progress in electronics, telecommunications and satellite technologies, permitting high capacity data transmission at very low cost, has resulted in the quasi abolition of physical distance. For all practical purposes, there are no more logistical barriers to information access and communication among people, institutions and countries

Changing education and training needs

A trend towards higher and different skills has been observed in OECD countries and in the most advanced developing economies, as a result of increased competition in the labor market and rapid change in economic structures. This is confirmed by recent analyses of rates of return in a few Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil and Mexico) which show a rising rate of return for tertiary education, a reversal of earlier trends in the 1970s and the 1980s.2 Moreover, in OECD countries, highly skilled white collar employees account for 25 to 35 per cent of the labor force.

A second, related dimension of change is the need to train young people to be flexible and to acquire the capacity to adapt easily to a rapidly changing world. Recent research carried out by Levy and Murnane on the skills requirements for the tasks performed in the US labor market shows the types of skills for which there is less demand or which have been taken over by computers and those for which there has been increased demand3. In their path-breaking study, the authors divided the tasks performed in firms into five broad categories:

- Expert thinking: solving problems for which there are no rule-based solutions, such as diagnosing the illness of a patient whose symptoms are out of the ordinary;

- Complex communication: interacting with others to acquire information, to explain it, or to persuade others of its implications for action; for example, a manager motivating the people whose work he/ she supervises;

- Routine cognitive tasks: mental tasks that are well described by logical rules, such as maintaining expense reports;

- Routine manual tasks: physical tasks that can be well described using rules, such as installing windshields on new vehicles in automobile assembly plants; and

- Non-routine manual tasks: physical tasks that cannot be well described as following a set of “if-then-do” rules and that are difficult to computerize because they require optical recognition and fine muscle control; for example, driving a truck.

The figure below shows trends for each type of task. Tasks requiring expert thinking and complex communication grew steadily and consistently during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The share of the labor force employed in occupations that emphasize routine cognitive or routine manual tasks remained stable in the 1970s and then declined over the next two decades. Finally, the share of the labor force working in occupations that emphasize non-routine manual tasks declined throughout the period.

Source: Reproduced from Levy and Murnane (2004), p. 50, figure 3.5.

Note: Each trend reflects changes in the numbers of people employed in occupations emphasizing that task. To facilitate comparison, the importance of each task in the US economy is set to zero in 1969, the baseline year. The value in each subsequent year represents the percentile change in the importance of each type of task in the economy.

OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which measures how well 15-year-olds in school are prepared to meet the challenges of today’s knowledge societies, is the only available international survey that comes close to assessing the effectiveness of education systems in preparing young people for the expert thinking and complex communication skills studied by Levy and Murnane.

PISA looks at students’ ability to use their knowledge and skills to meet real-life challenges, rather than to master facts or a specific school curriculum. The first round of PISA was in 2000. It covered several content areas, but focused more on reading literacy, covering more than 300,000 secondary-school students in over thirty countries (including a few non-OECD members). The second round, in 2003, focused more on mathematics, and included measures of problem-solving ability. The 2003 PISA results clearly show that a large proportion of the target population does not meet the expected standards. In OECD countries, an average of 25 per cent of the tested population have low levels of achievement (inferior to level 2 on a scale from 1 to 5). The results are much worse in developing countries. In Mexico, for example, 67 per cent of the students attain less than the minimal level; in Tunisia 75 per cent are in the same situation.4

The third dimension of change in education and training needs is the growing importance of continuing education needed to update knowledge and skills on a regular basis because of the short “shelf life” of knowledge. The traditional approach of studying for a discrete and finite period of time to acquire a first degree or to complete graduate education before moving on to professional life is being progressively replaced by practices of lifelong education. Training is becoming an integral part of one's working life, and takes place in a myriad of contexts: on the job, in specialized higher education institutions, or even at home. As Shakespeare wrote with prescience several centuries ago:

“Learning is but an adjunct to ourself,

And where we are our learning likewise is.”

In the medium term, this may lead to a progressive blurring between initial and continuing degree studies, as well as between young adult and mid-career training. Finland, one of the leading promoters of continuing education in Europe, is among the most advanced nations in terms of conceptualizing and organizing tertiary education along these new lines. Today, the country has more adults engaged in continuing education programs (200,000) than young people enrolled in regular higher education degree courses (150,000). But not all countries have achieved a balanced educational development as reflected in the qualifications of their labor force. While in Finland the proportion of the population older than 15 with secondary or tertiary education levels has increased from 12 to 70 per cent from 1960 to 2000, in a developing country such as Senegal it has grown only from 4.5 to 10 per cent over the same period.

From the student s perspective, the desire to position oneself for the new types of jobs in the knowledge economy provides a strong incentive to mix study program options and qualifications, often beyond traditional institutional boundaries. New patterns of demand are emerging, whereby learners attend several institutions or programs in parallel or sequentially, thus defining their own skill profiles in the labor market.

Another important consequence of the acceleration of scientific and technological progress is the diminished emphasis in tertiary education programs on the learning of facts and basic data per se. There is a growing importance of what could be called methodological knowledge and skills, i.e. the ability to learn in an autonomous manner. Today in many disciplines, factual knowledge taught in the first year of study may become obsolete before graduation. The learning process now needs to be increasingly based on the capacity to find, access and apply knowledge to problem-solving. In this new paradigm, where learning to learn, learning to transform information into new knowledge, and learning to transfer new knowledge into applications is more important than memorizing specific information, primacy is given to information seeking, analysis, the ability to reason, and problem-solving. In addition, competencies such as learning to work in teams, peer teaching, creativity, resourcefulness and the ability to adjust to change are also among the new skills which employers value in the knowledge economy.

The changing tertiary education landscape

New Forms of Competition. The decreased importance of physical distance means that the best universities in any country can decide to open a branch anywhere in the world or to reach out across borders using the Internet or satellite communication links, effectively competing with any national university on its own territory. With 90,000 and 500,000 students respectively, the [public] University of Maryland University College and [private] University of Phoenix have been the fastest growing distance education institutions in the USA in the past five years. The British Open University has inundated Canadian students with Internet messages saying more or less “we’ll give you degrees and we don’t really care if they’re recognized in Canada because they’re recognized by Cambridge and Oxford. And we’ll do it at one-tenth the cost.” 5 It is estimated that, in the US alone, there are already more than 3,000 specialized institutions dedicated to online training. Thirty-three states in the US have a statewide virtual university; and 85 per cent of the community colleges are expected to offer distance education courses by 2002.6 Distance education is sometimes delivered by a specialized institution set up by an alliance of universities, as is the case with Western Governor University in the US and the Open Learning Agency in British Columbia.

The proportion of US universities with distance education courses has grown from 34 per cent in 1997-98 to about 50 per cent in academic year 1999-2000, with public universities being much more advanced than private ones in this regard.7 The Mexican Virtual University of Monterrey offers 15 master’s programs using teleconferencing and the Internet that reach 50,000 students in 1,450 learning centers throughout Mexico and 116 spread all over Latin America. In Thailand and Turkey, the national open universities enroll respectively 41 and 38 per cent of the total student population in each country. Corporate universities are another form of competition which traditional universities will increasingly have to reckon with, especially in the area of continuing education. It is estimated that there are about 1,600 institutions in the world functioning today as corporate universities, up from 400 ten years ago. Two significant examples of successful corporate universities are those of Motorola and IBM. Recognized as one of the most successful corporate universities in benchmarking exercises, Motorola University, which operates with a yearly budget of 120 million dollars representing almost four per cent of its annual payroll, manages 99 learning and training sites in 21 countries.8 IBM’s corporate university, one of the largest in the world, is a virtual institution employing 3,400 professionals in 55 countries and offering more than 10,000 courses through Intranet and satellite links.

Corporate universities operate under one of any combination of the following three modalities: (i) with their own network of physical campuses (e.g., Disney, Toyota and Motorola), (ii) as a virtual university (e.g., IBM and Dow Chemical), or (iii) through an alliance with existing higher education institutions (e.g., Bell Atlantic, United HealthCare and United Technologies). A few corporate universities, such as the Rand Graduate School of Policy Studies and the Arthur D. Little School of Management, have been officially accredited and enjoy the authority to grant formal degrees. Experts are predicting that, by the year 2010, there will be more corporate universities than traditional campus-based universities in the world, and an increasing proportion of them will be serving smaller companies rather than corporate giants.

Franchise universities constitute a third category of new competitors. In many parts of the world, but predominantly in South and Southeast Asia and the formerly socialist countries of Eastern Europe, there has been a proliferation of overseas “validated courses” offered by franchise institutions operating on behalf of British, U.S., and Australian universities. One-fifth of the 80,000 foreign students enrolled in Australian universities are studying at offshore campuses, mainly in Malaysia and Singapore (Bennell 1998). The cost of attending these franchise institutions is usually one-fourth to one-third what it would cost to enroll in the mother institution.

The fourth form of unconventional competition comes from the new “academic brokers”, virtual entrepreneurs who specialize in bringing together suppliers and consumers of educational services. A few examples can be mentioned to illustrate this new trend:

- Companies like Connect Education, Inc. and Electronic University Network build, lease and manage campuses, produce multimedia educational software, and provide guidance to serve the training needs of corporate clients world-wide.9

- Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute coordinates and delivers degree programs from Boston University, Carnegie Mellon, Stanford University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for the employees of United HealthCare and United Technologies.10

- Nexus, a UK based company advertising itself as the “world’s largest international student recruitment media company”, organizes fairs in many East Asian and Latin American countries, bringing together higher education institutions and students interested in overseas studies.

- Web sites like HungryMinds.com and CollegeLearning.com act as clearinghouses between schools and prospective students.

- ECollegebid, a consortium of colleges and universities, matches student objectives and ability to pay for an education with the willingness of a tertiary institution to offer tuition discounts.

At the shadier extreme of the academic brokering industry, one finds Internet-based essay mills offering to help students with their college assignments. Defended by their promoters as useful and harmless research tools, they are under attack from the academic community who decries their capacity to increase plagiarism and cheating.

Some “traditional” higher education institutions have been quick to catch onto the potential of education and training brokering arrangements. St. Petersburg Junior College recently entered into a partnership with Florida State University, the University of Central Florida and the UK Open University to offer four-year degree programs at some of its sites.11 The University of California at Santa Cruz, having set up its own corporate training department ten years ago right in the middle of Silicon Valley, has established successful partnerships with a number of corporate universities, notably those operated by GE and Sun Microsystems, even managing to attract additional state funding on a matching grant basis.12

Changes in Structures and Modes of Operation. Faced with new training needs and new competitive challenges, many universities have undertaken important transformations in governance, organizational structure and modes of operation.

A key aspect has to do with the ability of universities to organize traditional disciplines differently, taking into consideration the emergence of new scientific and technological fields. Among the most significant ones, it is worth mentioning nanotechnology, molecular biology and biotechnology, advanced materials science, microelectronics, information systems, robotics, intelligent systems and neuroscience, and environmental science and technology. Training and research for these fields require the integration of a number of disciplines which have not necessarily been in close contact previously, resulting in the multiplication of inter- and multidisciplinary programs cutting across traditional institutional barriers. For example, the study of molecular devices and sensors, within the wider framework of molecular biology and biotechnology, brings together specialists in electronics, materials science, chemistry and biology to achieve greater synergy. Imaging technology and medical science have become closely articulated. Universities all over the world are restructuring their programs to adapt to these changes.

The new patterns of knowledge creation do not imply only a reconfiguration of departments into a different institutional map but more importantly, imply the reorganization of research and training around the search for solutions to complex problems, rather than the analytical practices of traditional academic disciplines. This evolution is leading to the emergence of what experts call “transdisciplinarity”, with distinct theoretical structures and research methods.13 McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, and the University of Maastricht in Holland were among the first universities to introduce problem-based learning in their medical and engineering programs in the 1970s. The University of British Columbia is promoting “research-based learning”, an approach linking undergraduate students to research teams with extensive reliance on information technology for basic course information. Waterloo University in Western Ontario earned a high reputation for its engineering degrees – considered among the best in the country – through the successful development of cooperative programs that integrate in-school and on-the-job training.

Even PhD. programs may be affected by this trend towards increased multi-disciplinarity. Proponents of a reform of doctoral education in the US predict that PhD. students will be less involved in the production of new knowledge and more on contributing to the circulation of knowledge across traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Realigning universities on the basis of inter- and multi-disciplinary learning and research themes does not imply only changes in program and curriculum design, but also significant modifications in the planning and organization of the laboratory and workshop infrastructure. From the Georgia Institute of Technology comes a successful experience in developing an interdisciplinary mechatronics laboratory serving the needs of students in electrical, mechanical, industrial, computer and other engineering departments in a cost-effective manner.14 A unique partnership bringing together Penn State University, the University of Puerto Rico-Mayaguez, the University of Washington and Sandia National Laboratories has permitted the establishment of “Learning Factory” facilities across the partner schools which allow teams of students from industrial, mechanical, electrical, chemical engineering and business administration to work on interdisciplinary projects.15

The evolution towards lifelong learning means that young high school graduates will gradually cease to be the primary clientele of universities. As a result, universities must organize themselves to accommodate the learning and training needs of a very diverse clientele: working students, mature students, stay-at-home students, travelling students, part-time students, day students, night students, weekend students, etc. One can expect a significant change in the demographic shape of higher education institutions, whereby the traditional structure of a pyramid with a majority of first degree students, a smaller group of post-graduate students, and finally an even smaller share of participants in continuing education programs will be replaced by an inverted pyramid with a minority of first time students, more students pursuing a second or third degree, and the majority of students enrolled in short-term continuing education activities. Already in the US, almost half of the student population consists of mature and part-time students, a dramatic shift from the previous generation. In Russia, part-time students represent 37 per cent of total enrolment.

Tertiary education institutions are also changing their pattern of admission to respond in a more flexible way to growing student demand. In 1999, for the first time in the US, a number of colleges decided to stagger the arrival of new students throughout the academic year, instead of restricting them to the fall semester.

In China, similarly, a spring college entrance examination was held for the first time in January 2000, marking a sea change in the history of that country s entrance examination system. Students who fail the traditional July examination will no longer have to wait a full year anymore to get a second chance.

Conclusion: New opportunities and challenges

The major trends and changes outlined in this article represent both opportunities and challenges for tertiary education institutions in developing countries, which are called upon to play a vital capacity building role in support of economic growth, poverty reduction, and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals.

On the positive side, the use of modern technology can revolutionize the way education is delivered, resulting in more and better learning opportunities. The concurrent use of multimedia and computers permits the development of blended pedagogical approaches involving active and interactive learning. Frontal teaching can be replaced by or associated with asynchronous teaching in the form of online classes that can be either scheduled or self-paced. With a proper integration of technology in the curriculum, teachers can move away from their traditional role as one-way instructors towards becoming facilitators of learning.

In a pioneer study conducted at the beginning of the 1990s, two professors at the University of Michigan, Kozma and Johnson, analyzed several ways in which information technology could play a catalytic role in enriching the teaching and learning experience. They suggested a new pedagogical model involving (i) active engagement of the students rather than passive reception of information, (ii) opportunities to apply new knowledge to real-life situations, (iii) the ability to represent concepts and knowledge in multiple ways rather than just with text, (iv) the use of computers to achieve mastery of skills rather than superficial acquaintance, (v) learning as a collaborative activity rather than an individual act, and (vi) an emphasis on learning processes rather than memorization of information.16

Web-based virtual labs, remote lab experiences and access to digital libraries are but a few examples of the new learning enhancing opportunities that increased connectivity can provide cash-strapped universities and colleges in developing countries. For instance, tertiary institutions with virtual libraries can join the recently established Online College Library Center which offers inter-library loans of digitized documents on the Internet. Even in traditional libraries, CD-ROMs can replace journal collections. Cornell University, for example, has created the Essential Electronic Agricultural Library , which consists of a collection of 173 CD-ROMs storing text from 140 journals for the past four years that can be shared with libraries at universities in developing country.

The open education movement, pioneered by universities such as MIT (Open CourseWare), Carnegie Mellon (Open Learning Initiative), Rice University (community-based learning object commons ), and Harvard University (special library collections) with funding from the Hewlett Foundation, offers the promise of extensive content and software resources that tertiary education institutions in developing countries could use and adapt to fit their needs. A Chinese consortium working in partnership with MIT has already established an expanded Chinese version of the Open CourseWare website. Users all over the world are leveraging the power of the Internet to form virtual communities of learning to help each other apply and further enrich available open education resources.