|

|

IV Lessons Learned by Universities

Lessons from Building a Research Network (SUDESCA) in Central America

by Leiner Vargas Alfaro, Academic Director, CINEPE-UNA,

Costa Rica

Abstract

The increasing role of innovation and innovation policies in sustainable development has been demonstrated by research activities in the Sustainable Development Strategies for Central America (SUDESCA) research network in Central America. The development of a common set of values and theoretical approaches to analyze those policies has been a specific focus topic in the SUDESCA network which includes research groups in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Denmark. The building of research capacities on innovation and sustainable development has been done under a particular set of conditions and it has, partially, achieved the initially proposed objectives.

The project

The project has succeeded in developing a network of researchers from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean focusing on rather new issues related to national, local and sectoral innovation systems and sustainable development. Even if the process of building institutional and individual capabilities has been interrupted prematurely by lack of funding, the lessons learned and the seed activities, which were carried through, have promoted new activities of applied university research, which have contributed to a redefined regional agenda for innovation and innovation policies.

The time framework and the available resources were quite limited in relation to the objectives of the rather ambitious research program, especially when considering the regional character of the research and the number of organizations involved. The coordination activities as well as the level of enthusiasm within the research groups have been quite different and, so far, the results also reflect these different levels of capacity building. The counterparts who benefited most were the International Center for Economic Policy (CINPE) and the National University (UNA) in Costa Rica in spite of the fact that the main focus of interest was Nicaragua. However, within a broader regional vision the agenda has been very much affected by nation state priorities.

The quality of the research in the network clearly improved, but it must be concluded that it takes a lot of time and long-term investments to produce important changes in the existing research agenda and the local research conditions in the Central American region. A focus on already existing promising clustering activities should be preferred to creating new programs based on very limited local capabilities. In this respect mayor lessons were learned from the experiences of the University of El Salvador.

The focus on sectors and issues of increasing political priority as environmental and local development were also sources of important lesson for the SUDESCA project. Applied research under a concrete and unifying framework such as the “systems of innovation approach” was also interesting. It has allowed the participating research groups to get into contact with new researchers and organization sharing common goals and methods.

Both the south and the north may improve their research capacity by network building and research cooperation so building capacity in developing countries is not just a transfer of a particular research technology, it is also a process of trust building and knowledge sharing and of developing a common research agenda. Learning from and with the south (the importance of intercultural learning) is a crucial lesson of the SUDESCA research network.

The network was developed with a balanced attention at both education and research capacity building. During the first phase the research activities concentrated on building basic statistics and an information background. Improving methodology as well as adapting “System of Innovation” concepts to the south were done during the first part of the second phase. The definition of local interest themes was done in cooperation between experienced researcher from Denmark and local people from Central America. During the whole second phase the learning tools were developed both within a common research activity and parallel PhD activities. This has created – particularly under the second research phase – increased trust between and within the group, not only within the south but also at the counterpart at Aalborg University (AAU).

Learning between cultures and within cultures was emphasized because of differences in language, local conditions and research orientation. For example, understanding the local conditions for research under different political and social situations was of crucial value. Qualitative research became an essential tool due to the difficulties in getting reliable statistics in Central America. Learning from doing and learning by interacting with local actors were crucial elements in the development of specific hypothesis and research cases.

Universities in Central America have been affected by different political and social events during the last century; particularly those countries north of Costa Rica due to the political and social conflicts in the sixties, seventies and eighties. They have lost much of the social trust in relation to some economic sectors and social groups. Local research capacity was reduced because a whole generation was lost and university budgets were constrained to a minimum under this political context. The concentration of SUDESCA research activities on innovation systems and sustainable development, both very relevant issues for the society, was a perfect opportunity to contribute to recovering the trust between university and society. Learning with and between social groups was an un-expected result of the project, particularly in Nicaragua, where the local group at the School of Agricultural Economics (ESECA) became part of national discussion. It was a relevant result also in El Salvador, but the results were mainly achieved by a non-governmental organization, National Foundation for Development (FUNDE). The Costa Rican case was a different because the university-society relation was clearly another from the very the beginning.

We have learned that University research agendas in developing countries should concentrate on issues where the society could benefit not only in macro-economic terms, but also in terms of local values and local groups. University capacity building is in this respect a sustainable way of affecting local capabilities in research conditions. But it is not a sufficient condition; countries need to stimulate a virtuous circle between research capacity building and development of local university conditions in order to create a sustainable process.

Finally, in relation to donor roles, we could say that a stable and long-term financial program is a very important aspect in order to get results. Once this is achieved, concentrating on local existing groups is an important aspect. Much donor help is used to build capacities almost from scratch; generally this only achieves meager results because it is a long-term process to construct local capabilities. Cooperation based on existing local capabilities should help to complement the local capabilities with external capabilities and thus reduce the risk of failure. One example is English language skills.

The Experience from an ENRECA Capacity Building Project

by Henrik Secher Marcussen, Professor, Dept. of Geography

& International Development Studies, Roskilde University

Abstract

In the light of globalization processes, it is in vogue by Western nation States to emphasize how vitally important it is to give top priority politically and financially to research and tertiary education. However, often such words are not met by deeds. In the case of the developing world, the need for getting aboard the globalization train is no less urgent. The increasingly important role of China and India in the global economy bears witness to the crucial role which so far only a few developing nations have succeeded in having.

Unfortunately, however, this aspect does not play an important role in Danish aid priorities, where support to primary education is targeted, while research is funded mainly through sector-wide programmes, through applications for grant through the RUF-system (Research Council for Development Research) or by means of the ENRECA form of assistance to capacity building.

Based on a review of a Danida supported ENRECA project in Burkina Faso, it is the objective of this contribution to try to assess how relevant and how effective this form of assistance to build research capacities in the developing world is. In doing this, the contribution tries to answer four interrelated questions: (i) Has the ENRECA project succeeded in meeting its own targets?, (ii) Has the project contributed to building national research capacities, filling a role in a national research and research policy chain?, (iii) Has the project contributed to improving on Danish aid performance in the country; and (iv) Has the project assisted Burkina Faso in meeting demands arising from an increasingly globalized world.

It is the conclusion of the article that, as based on the example reviewed, none of the four questions can be answered fully in the affirmative. Instead it is argued that a fundamental review of the ENRECA concept is needed, if this form of assistance may have broader impact, within the national context as well as beyond.

Introduction

In 2000, the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to commission a major review of Danish development research based on the ambition, as expressed by the then Minister of Development Cooperation, Jan Troejborg, that “In the future, research will have a much stronger position in Danish aid…” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2001, p. 8). In the Chairman’s Preface to the Commission Report, it is further stated:

“At a time of rapid change in the world, and also about greater uncertainties about future development trends, it was felt opportune to appraise the role of Danish development research sector and the contribution through research, teaching and consultancy to international as well as Danish development goals, and to formulate a new strategic framework for future Danida support to guide participants in the sector.

Hence the Commission was established to learn whether anything could be done to improve learning for policy making in a rapidly changing world” (Ibid., p. 9).

The Commission report is thus based on the observation, that “…the world faces unprecedented challenges and demands for new knowledge”. And the report continues: “…knowledge is growing exponentially. The possibilities are boundless and exciting: in electronics and information technology; in biology and genetics; in materials science; in energy; even in social science.(…) The risks are real that new knowledge will increase world inequality and even deepen poverty” (Ibid., p. 13).

However, when it comes to outlining what the new vision may entail, the ambitions are dramatically reduced. Development research is about meeting development aid needs, reflecting the principles of Denmark’s development policy, and every Danida funded research effort will in the future be expected to underpin and support Danish development aid needs, ensuring an improved aid performance.

This is further corroborated in the official presentation of the overall objective of providing development research as well as in the changes in the Danish institutional development research and grant system, which has been introduced as a follow up on the recommendations made in the Commission report.

In the official presentation of the general objective of funding development research, it is stated:

“Support to development research and building of research capacity in developing countries follow the overall principles of Danish development aid. The purpose is, therefore, to contribute to fighting poverty through the building of new knowledge and capacity within relevant disciplines and areas. Development research is thus not an end in itself, but an instrument directed towards achieving the overall goals” (Research. Presentation of the Danish system of support for development research, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ web site, 2005. Translation mine).

And in the same presentation it is stressed in presenting the role of the new RUF (the Council for Development Research), that it is the objective to “ensure a continuously high professional research quality standards and to strengthen the strategic and instrumental aspects of development research” (Ibid.).

However, within the reform measures introduced following the Commission report, the ENRECA concept for supporting research capacities in the developing world remains as an important vehicle.

The ENRECA concept

The ENRECA programme was the subject of an independent evaluation in 2000. The conclusion of the evaluation was that the programme was found very valuable and the evaluation strongly recommended its main principle of building capacities through twinning should be continued. The evaluation also made a number of recommendations, in particular that closer links between the programme and other Danida funded activities, including sector wide programmes, should be strengthened.

Also the Commission in its report finds that “ENRECA is an innovative programme, but is often not related to the aforementioned programmes (the other Danida funded activities, my remark) and, on its own, is not a sufficient response to the urgent need to strengthen the research and innovation system in Denmark’s partner countries” (The Commission Report, 2001, p. 19).

The Enhancement of Research Capacities in Developing Countries was established by Danida in 1989. It is for Danida a main form of assistance to research and tertiary educational institutions, carrying with is a funding of close to DKK 60 million for nearly 50 different projects, most of which located in a partnership constellation within Danida’s so-called programme countries, and most of which in Africa. The programme includes a widely scattered fields and themes, however projects within health and agriculture being the dominant ones. Typically, an ENRECA programme is expected to have a duration of around 12 years, to ensure sustainability of activities, divided into three four year phases, running with a budget of around DKK 1.5 million per year.

It is the ambition through this partnership, or twinning arrangement, between Danish research institutions and research institutions in the developing world to provide assistance to capacity building at institutional and individual levels. However important the activity is within Danida’s overall assistance to research19, yet it is a very marginal activity within the overall Danida portfolio.

When the ENRECA programme was conceived, only few at that time discussed the process of globalization or the challenges which this process would pose for the knowledge based economy. In that light, it is obviously not fair to compare the programme, its status, function and outcome to the requirements and challenges of a globalized economy, in which the developing countries with few exceptions generally do not yet take part, yet it is not entirely beyond the point to address this issue seen on the background of the lofty goals and introductory justifications in the Commission Report, quoted above.

But it should be stressed that the ENRECA programme was seen as an instrumental effort in its own right to improve on quality of research and building research capacities as measured by own standards. Still it would also be an additional advantage if such capacity building could assist in ensuring better performance in Danida assisted programmes, although this was not a sine qua non.

The challenge for an ENRECA programme in an African context is no small task. Although highly varying, existing research infrastructure and capabilities are extremely weak, with a tendency also of reflecting different priorities and traditions of the former colonial powers. For instance, assisting primary, secondary, even tertiary, education was a much more given form of policy in former British colonies than it was in former French colonies (where the elite was educated in France at French universities), as reflected in better educational infrastructure established in both Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania20.

To an extent, the situation with regard to teaching and research in Africa also reflects the often more generally made observation that the African continent is on the margins of most things. The optimism and the dramatic growth processes witnessed in South East and South Asia are a far cry from what is seen in Africa. In this context, a main problem seems to be how to avert further marginalization, socio-economic differentiation and global inequities, with Africa still representing the continent so difficult to identify on the bandwagon of growth and prosperity.

Among the pertinent questions to pose could be: How to support capacity building that will assist Africa jumping on the bandwagon? Should some of Danida’s aid priorities be redirected also towards the tertiary educational sector (at present only given priority to primary education, by means of sector programmes in selected programme countries)? And is an ENRECA programme an adequate remedy or instrument to be a factor within this challenge?

Assessing the experience from an ENRECA project in

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso belongs to one of the poorest countries in the world, according to both the World Bank World Development Report and the UNDP Human Development Report. The country is landlocked and heavily dependent on its natural resources for the survival of its inhabitants, most of whom live in a rural setting. The country’s productive resources are extremely limited, with cotton production together with mining as the most important ones. In addition, migrant work in the neighboring coastal nations, such as Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, are providing vital remittances of cash back to the mainly rural families, ensuring a crucial injection of cash into an economy which is only integrated into the market economy to a limited extent. – Aid provides another vital means for assisting the government in running its investment programmes and ensuring a certain very basic provision of health, education and other social services, as only limited sources of state revenue are present.

The Burkinabe economy is thus highly fragile, and in addition extremely vulnerable to climate variability. Situated on the border of the most drought prone areas in Africa, the Sahel, output from the rural economy is fluctuating widely with rainfall patterns, where only rainfall well above a long-term average may secure the livelihood of its inhabitants, while in periods of weak rainfall, even drought (which is a recurrent phenomenon), poverty and famine may prevail.

It is in part on this background that the current ENRECA project has been formulated, trying to address two main development issues (although at a modest scale, within the financial provisions of the project type): On the one hand, the need to strengthen research, teaching and training within multidisciplinary environmental research, supporting the university departments ability to identify main developmental problems related to environmental degradation within the rural economy, and study these with an intention to be able to address and propose more adequate and suitable solutions to degradation issues. On the other hand, the need to address a basic and more widespread problem in the country, namely that Burkina Faso has only limited human resources at its disposal, taught and trained and with formal degrees enabling them continuously and consistently to educate new cohorts of young graduates, who can further assist the country in its development efforts.

While the situation in Burkina Faso in nearly all aspects is very basic, the general university characteristics are not completely beyond comparison with many other universities in the Francophone area. To a certain extent, at least, it may thus be said that the experience derived from the Danida supported ENRECA project may not be out of tune with the situation characterizing other universities in Francophone West or Central Africa.

The two universities in the country – Universite de Ouagadougou and the Polytechnic University in Bobo Dioulasso – are established within a French academic tradition and have only been in existence for a relatively short span of years, the Polytechnic University in Bobo Dioulasso being the most recent one, established in 1994. Although the two universities in recent years have received support from a number of donors, the funding from government sources are very restrained, salaries to teachers, researchers and other staff are very low, in most cases forcing staff to supplement income from more than one job position or, for researcher and teachers, in doing consultancies21, infrastructure provisions at the universities are very basic and the universities have only few among its teaching and research staff with doctoral degrees and employed at professorial levels. This also means that only few doctoral programmes exist, because such programmes require teaching and research staff with qualifications at doctoral/PhD levels. A consequence of this is that continuously, doctoral degrees are frequently sought abroad, in particular in France, the former colonial “mother” country.

The ENRECA project reviewed has tried to address some of the pertinent issues identified above, in connection with the two partner institutes, the Department of Geography at the UFR/SH22 at the University of Ouagadougou, and the Institut of Rural Development at the Polytechnic University at Bobo Dioulasso.

The project commenced in 1994 and has been running for two periods, and is now in its final, phasing out stage, ending as of end-2006. The total amount granted for the project by Danida has been in the tune of around DKK 13 million.

Within an overall objective of strengthening multidisciplinary research and education at the two institutions, the ENRECA project has more specifically targeted:

- The creation of a GIS (Geographic Information Systems) and Remote Sensing laboratory;

- The introduction of basic as well as more advanced courses in GIS and RS techniques, for students and teachers, trainers and researchers;

- The support to conducting field studies and field surveys for students preparing for their Diploma or Masters work;

- The holding of specialized courses on field work methodology, data treatment techniques, the use of netbased data and literature information; writing skills and (English) language training;

- The support for research conducted by research and teaching staff;

- The participation for research and teaching staff in relevant international conferences, particularly those held in the region;

- The holding at the University of Ouagadougou of regional conferences, presenting outcome of ENRECA supported research;

- The holding of workshops targeting policy decision makers and (Danida) aid personnel;

- The publication in refereed journals and other sources of publication of research results, following the French peer review-system CAMES;

- The jointly pursued research between Danish and Burkinabe partners;

- The support for PhD studies for selected Burkinabe researchers.

What have, then, been the achievements, as measured against the formulated expected outputs in the Project Document?

A fully equipped and functioning GIS and RS laboratory has been created and maintained, where more than 30 undergraduate students have been trained each semester in basic GIS techniques. In addition, advanced courses have regularly been offered to senior staff. Covering modest costs of doing field studies, collecting data for Diploma and Thesis work, has contributed to more than 40 students written projects, which generally have received higher than usual marks, and where candidates passed these examinations are high in demand on the Burkinabe labor market. Senior teachers and educators have been offered training in the new technical opportunities, which GIS, RS and other IT techniques provide, however only few responding to this. A substantial number of articles have been published in CAMES peer reviewed periodicals, increasing publication frequency compared to earlier. Still, quality of research has only improved slightly, which to an extent is related to a particular (perhaps French inspired) perception as to what research means, namely to conduct field work, being in the field for prolonged periods of time and to collect enormous amounts of empirical information and data, resulting in more descriptive rather than analytical forms of research. Two PhD. candidates are in the process of finalizing their dissertation work, being ready shortly for the defense. Only marginal collaboration on research has been seen between Burkinabe and Danish colleagues and only a couple of joint publications, none of which in peer reviewed journals.

The overall assessment is believed to be positive, as achievements seem to be at par with other ENRECA projects. Yet, these achievements may seem modest as compared to the funding gone into this kind of project and, in particular, the opportunities offered, which have not always been well received or welcomed.

The latter issue is touching upon a wider set of problems in partnership programmes, in which unequal partners participate, however based on the ideology of partnership, colleagueship and equality – which can only be assured in the very long term. And the more basic conditions at the outset, the more time is needed, perhaps in cases awaiting a whole generational shift, in attitude, motivation and career ambitions.

This seems at least to have been the case for this ENRECA project, where the baseline situation was more difficult than anticipated, and more problematic than an initial institutional assessment was able to reveal.

Immediately after the commencement of the project in 1994, the one partner institution, Institut de Developpement Rural, was transferred to the newly created Universite Polytechnique in Bobo Dioulasso, and every staff had to move to the province and into a university, which barely existed as no infrastructure was then in place. Logistically this constrained collaboration and communication tremendously, resulting in the Universite Polytechnique never really getting into the project focus. But in addition to this, the two partner institutions proved to be far more weak than foreseen.

While this may seem to have offered excellent justifications for an ENRECA project type, providing assistance to university institutes in dire need of such assistance, the result however was a far more strenuous collaboration modus, a constant uphill battle, than anticipated. In addition, the project ambitions and the possibilities it offered were not always received with the expected understanding and approbation from, in particular, senior staff members. Rather to the contrary.

To senior staff members the expectations were that this project would provide a kind of social development fund, which could compensate for the otherwise low university salaries. While the project has included output based remuneration criteria, such paying premiums for publications accepted in peer reviewed journals, the project was not able to pay topping up of salaries (without functional duties attached to it) or cover per diems or travel claims in the order anticipated by colleagues. In general, the assumption of the project, that the opportunities offered would be viewed as intended, namely as an opportunity for strengthening career options also for senior staff, this was not exactly seen in the same way, as senior staff in cases did not show keen interests in improving their career prospects. Nor did they, in cases, seem to acknowledge and encourage that younger staff much more eagerly tried to explore the possibilities offered by the project.

One lesson from the project in this regard is that the generational problem is a serious one, and one which is particularly difficult to tackle. The younger generation has aspirations and ambitions, because to them knowledge means power – and improved likelihood of a change in living conditions. For the older generation, knowledge gained by the younger generation may mean loss of power, thus threatening a hierarchised and authority based stiff university system.

For the Danish project management team this implied a number of constant challenges, which were not always overcome in the most elegant fashion, if overcome at all. At times frustration on both sides resulted in open conflicts and threats of interrupting the project, mainly due to an activity level too low compared to work plans and agreed upon decisions, seldom sustained and implemented. In this non-decisions were good, even better than decisions, as everything seemed always to be (re)negotiable. In many ways this was also a clash of cultures, which in short may be expressed in the form of French inspired culture (and language), mixed with Burkinabe laissez faire and confronted with Danish rationalities, including expectations as to meet more or less similar rationalities in the partnership constellation.

To sum up, however, trying to answer one of the questions posed initially, outcome from the project has not been negligible and largely results have met several of the output criteria listed. As such, the project has not been failing, perhaps also largely corresponding to results from other comparable ENRECA projects. Yet results may not have been that impressive compared to the costs, energies and time put into it and may have left partners slightly disappointed.

The ENRECA project as assessed in a national context

While the ENRECA project by and large has demonstrated that many of the outputs listed in the Project Document have been met, at least to a certain extent, still it may be questioned whether the project is sustainable in the longer term. This aspect has to do with both the way in which the partners and the partner institutions view the project now and beyond the formal termination of the project towards the end of 2006, and the broader national conditions for sustaining an ENRECA kind of project activity.

As already touched upon in the above, the expectations of staff at partner institutions, in particular senior staff, were that the project would enable to make a contribution to the meager salaries paid within the university system, seeing the project more in line with a “social development fund” rather than as a vital career vehicle. This again lead to numerous discussions and conflicts over means and end in the project and surely did not encourage general motivation or levels of activity. As mentioned by a Director attached to one of the institutions when the heating turned on: “This is not the first project of its kind, and certainly will not be the last”.

While these types of discussion left the project management in a role as controllers more than partners, and where the local management team continuously resisted playing its controlling and management role, the whole subject of discussion and controversy should be realized as a real one: No research capacities can be built, which will prove viable and sustainable, unless dedicated and motivated people are in place. Motivation and dedication, however, in a developing world context cannot be separated from the basic fact that even university staff have to live, survive and sustain the livelihood of their families, and if government regulated (university) salary structures do not allow for that (while donor driven consultancy remuneration structures do), then any ENRECA project (in which topping up of salaries are prohibited by the very same donors paying excessive consultancy honoraria) is deemed to run into similar kinds of trouble experienced in the present project. University staff is no more philanthropists than any other salaried personnel!

In this Catch 22 situation, the ENRECA project failed to address a pertinent problem, which in the course of events took over as a main controversial issue, repeated again and again, constraining, even hindering, that outcome of project investments resulted in more convincing – and sustainable results. And to the extent results from the project will be sustained, in particular the GIS and RS laboratory, this is still expected to have an effect primarily within the university system itself, rather than beyond, although in this phasing out stage, in which the project currently is, exactly efforts in trying to market and sell the services and the courses offered by laboratory staff, are seen as a potential income generating device.

But the limitations put on a project of the ENRECA type, situated in a rather typical African context, with low remuneration and incentive structures and with the funding of universities not high on the government budget spending agenda (or given priority by donors generally), these are also the limitations which constrain this form of capacity building in fulfilling their more ideal functions, namely situating such form of assistance in a larger chain structure, reaching from institutes and departments, to university level, and further on to line ministries, addressing not only research per se, but also research policy issues, research administration and, not the least, research results utilization, to the benefit of society at large.

This is an ideal model, which has been discussed for years and on the background of which “good” research assistance to broadly based capacity building in the developing world is measured. Because in this thinking, assistance to building capacities in the “local space”, at university levels, matters little, however valuable it may be seen, if not situated within and influencing the broader, nationally based research infrastructure, chain of management and decision making structures.

Within such a comparison, the ENRECA project in Burkina Faso has failed to live up to such broader national ambitions and objectives. Although the project has not been conceived of in this perspective, still the national macro-economic limitations for both university funding and the maintenance of realistic remuneration and incentive structures for university salaried staff have prevented such broader national ambitions in being met while at the same time casting in doubt prospects for viability and sustainability at university/departmental level itself.

Relations to other Danida funded aid activities

Another measure of relative success would have been if the support to capacity building at the two universities in Burkina Faso had resulted in a much more intimate working relationship with the Danida technical staff at the Danish Embassy in Ouagadougou or resulted in research results feeding directly into relevant Danida funded aid activities.

As may be recalled from the above, exactly this point seeing research capacity building as closely related to other Danida funded activities has been raised as a critical issue in the ENRECA evaluation from 2000, and reiterated as a very important element to remedy in the future, as mentioned in the Commission Report from 2001.

Certain efforts have been made on behalf of the ENRECA project in the course of its lifetime to establish better relations with both the Danish embassy and with Danida funded projects. A number of workshops have been held, presenting outcome of research, to which embassy staff has been invited, together with other stakeholders from both the aid and research community in Ouagadougou. The purpose of these workshops have been, as also reflected in titles of the workshops held, to try to build networks and relationships in order to bridge between research, aid and policy. In addition have ENRECA staff taken the initiative to meet with Danish mission staff, in particular with those professionally responsible for projects within rural development or natural resource management.

With regard to the Danida funded projects in relevant sectors, the ENRECA project has directly established through officially signed Memorandums of Understanding between project management and ENRECA researchers links which were expected to be reasonable committing and resulting in closer collaboration.

In general, such avenues for improved relations and efforts in having research to feed into the policy process have, however, shoved only limited success. The reasons for this may be many.

On the one hand, it may have been the case that the researchers have not been able to communicate effectively their messages, in forms suitable for policy making or project management. Also the researchers may have been reluctant in establishing more formal relations of collaboration in view of the stricter requirements for producing useful results within fixed periods and deadlines. And the researchers may have been viewed as less relevant and qualified to do the jobs requested, compared to others, for instance consultants or consultancy firms.

On the other hand, it seems obvious that on the “recipient” side, the situation is often characterized by excessive work loads and a time (as well as disbursement) squeeze which leave little room for afterthought and experience gathering. Awaiting responses from researchers who often deliver such with certain delays, or demanding more time to dig deeper into problems, which have shown far more complex than anticipated, may not be seen as facilitating collaboration and mutual trust. To this come a turnover in personnel at embassies and projects which in many cases require that efforts in establishing networks and partnerships need to start all over, when such relations have finally been established with some individuals, only to see them transferred to a new posting within a relatively limited time interval.

To conclude, with regard to establishing more synergies and improved, effective working relations between an ENRECA project and stakeholders within the aid, policy making or research community, the experience from Burkina Faso shows, that there is still considerable scope for improvements, and that the recommendations both of the 1990 ENRECA Evaluation and the remarks by the Commission Report in 2001 are still valid.

ENRECA projects: Building capacities to respond to

global challenges?

The ENRECA project in Burkina Faso was formulated in the early 1990s and commenced its activities in 1994 at a time where globalization and the quest for feeding into a globalized knowledge economy were still issues which seemed to belong to the future, at least which did not take up as much place in current discussions and rhetoric as to-day. In retrospect, the ENRECA project in Burkina Faso may thus be termed an “ENRECA Classic” project. On this background it may seem ridiculous to try to assess the extent to which an ENRECA project could play a role in such global challenges, even more so an ENRECA project in one of the world’s poorest nations, Burkina Faso.

However, how far-fledged this may seem, still this is a perspective raised in the literature more generally, as a main justification for also this kind of capacity building project. Such views are reflected in the Commission Report quoted above and, for instance, when Thulstrup (1998, p. 90) in his introduction to an article states that “The rapid technological development of recent years has produced numerous research based products without which developing countries will be unable to compete in increasingly global markets. Technological progress has important positive aspects. In many cases the new technologies offer unique development opportunities for countries in the Third World”.

Although the best performing part of the ENRECA project in Burkina Faso consists of the establishment of a well functioning GIS and RS laboratory, using some of the most recently available ecological monitoring technology at a scale useful for university teaching and research purposes, yet it is more than doubtful that this aspect of the project, at least at present, may contribute to Burkina Faso facing some of the challenges posed by an increasingly global economy. This is, however, closely connected to the capacity building project not yet forming part of a wider national capacity effort (as referred to above).

But it is also a result of a way of conceiving research assistance as centered around aid and aid needs, and seeing research strengthening and capacity building as instrumental in assisting aid projects becoming better performers, rather than seeing the support for research as having a value in itself, as contributing to a broader defined economic growth process.

Thulstrup (Ibid., p. 91) touches upon similar aspects, when saying that:

“Research in many developing countries (particularly in Africa) is donor driven. Consequently, the changing relevance of different research fields in a given country is not only of national interest: it is also important for donor agencies.

Many of the large donors still have a strong preference for research capacity building in tropical health, tropical agriculture, and development studies, often applauded by powerful donor country lobbies in the academic environments of these traditional fields. Today, however, it is increasingly clear that the needs for research capacity building in the Third World are much wider”.

Building research capacities in a wider sense means addressing a much more fundamental, even imperative development issue, namely looking critically into prevailing, mainstream development strategies, which are nowadays supported by the whole range of donor agencies, whether multilateral, bilateral, NGOs or any other donor variant, emphasizing the very same development priorities (and often with the very same approaches and means).

Needless to say, aid in support of poverty eradication, support to good governance, democratization, decentralization, empowerment, participation, etc. cannot, and should not, be basically changed, as seen also on the background of the tremendous efforts done by donors and recipient governments alike (and also results coming forward), but why all donors should overcrowd the middle field in a way as of present, seems less obvious and justified. And why support to research capacity building should be perceived of as mainly seen within the same light and scope, aiding aid to perform better, also seems less obvious.

The clear leaning in the Commission Report, and its subsequent adaptation in Danish research policy practice, may here be viewed with particular reservation, because research capacity building will never meet its fundamental societal goal, including building capacities for meeting the challenges of the global economy (not to talk about having a place herein), without seeing capacity building in a broader perspective, more delinked from the specific requirements of the aid sector itself than at present. Seeing research capacity building mainly as mirrored on the requirements of the aid sector seems to be a misleading perspective, at least viewed in a wider national and international perspective.

And instead of mainstreaming all aid towards the common objectives, as set forth in the Millenium Development Goals to be reached by 2015 (however laudable this effort is), a greater variability and experimentation may be warranted, where the economic growth imperative be brought back in. No knowledge based economies may see the light of the day unless economic growth broadly speaking (not only “pro-poor growth”) is (re)introduced, the material productive fundament on which economic sectors develop, creating inter-sectoral linkages through effective demand in one sector for the trade and services in another, creating work places and employment, in domestic as well as export sectors, salaries, demand for consumer goods and taxable incomes with which, eventually, a state revenue can be gained, affording salaries paid based on which families can live and strive, etc., etc. Although this may also be the stated end-goal of much aid programmes, yet the focus is at present not on how best to create dynamic economic growth processes.

For research capacity building to be effective, in support of countries overall growth potential, rather than only assisting aid in becoming better, there seems to be a need for getting beyond poverty reduction per se, in combining efforts in reducing poverty with a fundamentally new drive towards more dynamic and qualitative economic growth processes.

Conclusion

In responding to the four initially posed questions, it may be concluded that in reviewing the ENRECA project in Burkina Faso, many of the objectives set forth have been met, to a certain degree, at least. On this basis, and as compared with other ENRECA projects, outcome of efforts is not insignificant.

At the same has the review shown a number of constraints and difficulties that may be typical for other ENRECA projects as well, which are closely linked to differences in perception of the project, its objectives, ambitions and working modalities. The perceptions of these issues differ widely between partners and tend to create constant problems. Such differences are in particular fostered by prevailing meagre remuneration and incentive structures at universities in the developing world, that make it difficult for research and teaching staff to sustain a decent living. Instead, externally funded research capacity building programmes are often seen as a source of supplementary income generation, rather than – as assumed in the project logic – as a means of improving academic career opportunities.

The assessment above has also shown that the ENRECA project has had limited impact in supporting national research capacity building efforts, although a potential exists within the established GIS and RS laboratory and its technological and human resource means.

While much of the justification for an ENRECA support type of activity is linked to aid practice, in this case linked to Danida funded aid programmes in Burkina Faso, also this aspect has not been faring in a particularly impressive way.

Finally, the ENRECA project has not succeeded in making Burkina Faso able to better respond to the challenges of a global knowledge economy which, however, may also be seen as far out, as this was not targeted in the original conceptualization of the ENRECA project, which may be termed “classic”. Yet, also this aspect ought to be included when formulating new, future research capacity building projects, whether in the form of a modified ENRECA type project, or in inventing completely new forms of assistance.

Thulstrup (1996) is suggesting the following levels, or stages, in a research capacity building effort, reaching from the more basic, partial capacity building within a given field, to a broader national capacity building outcome, seen as the ideal end-goal of research capacity building efforts:

- Partial research capacity in a given field is reached when researchers in that field are able to carry out research at the international level in cooperation with experienced researchers elsewhere;

- Complete research capacity in a given field is reached when researchers are able to perform all aspects of research and related training in the field, from the planning process to the dissemination of results at the international level;

- National research capacity is reached when a country is able to prioritize research activities; to effectively provide support for selected research projects; to monitor and evaluate research; to train, attract, and keep good researchers in the country; to create conducive research environments; and to apply research outcomes – both in the form of research training and results – for national development.

Seen on this background, the ENRECA research capacity building project in Burkina Faso can be seen as having contributed to the first two items, and probably more to the first one rather than the second one, while the third aspect is largely untouched by the project. In this connection it may also be said, that there is quite a quantum leap between the first two and the third ambition/objective. Indeed, a leap which seems rather far away in a distant future for a country such as Burkina Faso, where everything continuously is very basic.

However, the assessment of the ENRECA project in Burkina Faso has, perhaps, also raised the issue as to whether the ENRECA concept is an appropriate, adequate and timely tool for meeting the variety of goals, which present day developing countries are facing. The ENRECA concept may assist in building capacities in a particular field, and may do this very well. And the ENRECA concept, particularly in view of the implementation of the recommendations of the Commission Report, may also be an adequate tool for building capacities that may help Danida funded aid projects and programmes perform better.

But in meeting the broader issues associated the challenges of globalization or assisting developing countries (particularly in Africa) in having a place within this global economy, the ENRECA concept clearly falls short of expectations. In this respect there is need for new innovative thinking, and there is a need for new concepts and new modalities of assistance.

Such new thinking may take on two forms: On the one hand, the currently applied ENRECA concept should be reviewed and perhaps modified in order to ensure that not only (Danish) aid requirements for improved performance are met, but also that the national research capacity building effort is much more highlighted and prioritized. Indeed, the latter ought to be the primary objective to pursue.

On the other hand, there is obviously a need for revising aid strategies aimed at improving countries in the developing world in being better able to respond to the challenges of the global knowledge economy, and assist them in seeking a place within this perspective of globalization. This may be reached through aid, through supporting the countries role in WTO negotiations, in trade and export orientation. But it may also be needed more specifically and directly to target high quality, technologically advanced research and tertiary education in general.

At present, a few educational sector programmes are being developed (or at their start of implementation) for Danida assistance, but only targeting primary education because this is seen as directly connected to the main goal in Danish assistance of poverty eradication.

But there is a need to see research and education in more holistic terms, also including the wider and still more compelling development issues.

Recognising that it is not possible (even warranted) to redirect completely Danish aid practice and strategies, nor to expect that Danida can take on each and every challenge the developing world is facing to-day, focus ought to shift towards the Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Development, which is conspicuously absent in this discussion. Although the Ministry may be seem to be a natural partner, perhaps together with Danida with its profound knowledge of and experience from working in the developing countries, there is no indication that the Ministry wishes to play a proactive and effective role in this field.

Despite Government proclamations about wishing to see Denmark on top of a globalized world, at the forefront of international competition due to our swift responses to the challenges of the global knowledge economy, yet this has not been followed by corresponding strategic developments or funding possibilities. And neither has it been followed by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Development formulating how they may perceive assistance to tertiary education and partnership building between knowledge centres in Denmark and abroad (including countries in the developing world) may assist also Denmark in fulfilling the role, the Government says it wishes to see.

There is, obviously, a dire need for a new strategic turn, followed by concrete initiatives and activities.

References

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2001: Partnership at the Leading Edge: A Danish Vision for Knowledge, Research and Development. Copenhagen, the Ministry and Danida.

Forskning (Research). Ministry of Foreign Affairs web site, August 2005.

Thulstrup, E. W., 1996: Strategies for Research Capacity Building through Research Training. In: Thulstrup & Thulstrup, 1996: Research Training for Development, Roskilde University Press,Copenhagen.

Thulstrup, E. W., 1998: Evaluation of research Capacity Building in the Third World. Knowledge and Policy, Winter 1998, vol. 10, issue 4, 90 – 101.

Notes

19 In 2000, the Danida outlay for research amounted to a total of DKK 318 million, of which the contribution to the international CGIAR system amounted to DKK 130 million, the Council for Development Research DKK 49 miillion and contributions to centres and networks a total of DKK 80 million.

20 As an indication of this, Ghana had its first Secondary School built in 1917 in Achimota, feeding into the University of Ghana, Legon (located a kilometer away) constructed as an independence gift from Britain ahead of the formal Independence in 1957.

21 Often such consultancies are paid for by donors, including Danida, at rates which compared to salaries received at the university, may seem excessive, generally disrupting, or at least making it very difficult to maintain an ambition about creating sustainability through full time staff, working full time, fully devoted as well as fully remunerated, at least to an extent where a decent living is ensured.

22 UFR/SH, meaning Unite Formation Recherche/Sciences Humaines, is the organizational form under which former institutes/departments are grouped after a university reform in 2000.

Globalisation of Tertiary Education and Research in Developing Countries – The Malaysian-Danish Experience

by Agamuthu Pariatamby, Professor and

Randolph S. Jeremiah, Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract

In 2000, the Danish Cooperation for Environment and Development (DANCED) funded a capacity building project at Malaysian universities in environmental management and sustainable development as a second phase of an earlier effort to develop the resource base of Danish universities in assisting developing countries manage their environmental needs. Fifteen academic staff were exposed to education and research in Denmark and over 60 staff participated in various workshops on pedagogical approaches and in technical areas organized with the assistance of Danish universities. Twelve course modules utilizing problem-based methodologies were collaboratively developed among Malaysian universities. These modules, with the extensive use of 38 case studies, have been successfully integrated within numerous master and undergraduate programmes on environmental management and technology. Eighteen joint research projects were funded to support case studies development. Thirty-nine postgraduate students experienced problem-based learning in real-life projects during three joint courses that were organized with students and faculty members from Denmark. These students gained intercultural knowledge and were exposed to Danish teaching methodologies. The courses received enthusiastic response and subsequently two more courses were organized after the project ended. External stakeholders, as the end-user of university graduates, participated in the planning process for course module development and in other project activities whereby they have built their own capacities and a closer relationship with universities has been developed. DANCED’s support framework has also included universities in southern Africa and Thailand. Under this umbrella, a linked network was developed between the 19 universities to support education and research initiatives. Seven research networks were established and now link researchers from these four countries. In 2002, Malaysian academics gained the opportunity of contributing towards a joint declaration on higher education in sustainable development, which was presented at the World Summit for Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. Overall, a steady exchange of knowledge and experiences in environmental management was achieved. Malaysian universities have developed better capacity, intra and inter-institutional frameworks for collaborative teaching and research, and mutually recognize each other’s strengths. The relationship with Danish universities is now sustained under new phases of co-operation under projects funded by the European Union and also through other initiatives. From the Malaysian perspective the programme is considered a success in bringing a paradigm shift in teaching methodologies. It has created numerous linkages for career development and a scientific collaboration in research.

Introduction

Demands for tertiary education are increasing in view of the changing social and economic structure in many developing countries including Malaysia. A knowledge-based economy is envisioned as a goal towards achieving a developed nation status and a more competitive economy with less reliance on the industrial and agricultural sectors. With the globalisation of economies, opening of new markets and a higher presence of multinational organisations in many Asian countries, both employer and employee demands for higher qualifications are being experienced. Universities have traditionally played the role of providers of education and although this function remains the same today, graduates have greater expectations for the type of postgraduate education being offered. Universities have acknowledged the need to re-orient their education policies and enhance their capacity not only in re-training academia and in increasing the quality of programmes through the application of new methodologies, techniques and knowledge but also in utilising available tools in information technology and communication. In view of this, the globalisation of education can be seen as a strategy in response to these needs. Globalisation of universities means a growing interdependence and interconnectedness of the globe through increased movement of students and academics across boundaries with the lowering of barriers for their movements and better international communication (Verma, 2004). In a developing country, globalisation of education offers the opportunity of shared access to resources and can encourage the transfer of technology, innovative techniques and methodologies. Overall, this will help fill the gaps in knowledge and increase the capacity of education programmes at institutions within these countries. This paper aims to present some experiences, achievements and lessons learnt from working within an international collaboration aimed at developing the capacity of Malaysian tertiary education. It also poses some challenges for future collaborative activities between institutions especially from developing and developed countries. The Malaysian-Danish collaboration under the Danish Co-operation for Environment and Development (DANCED) programme is used as a case study.

Background

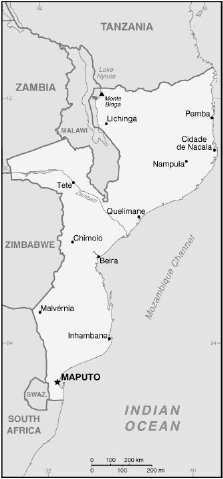

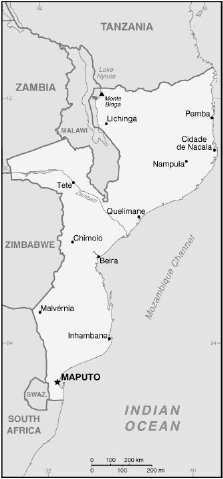

A specific economic framework for financing Danish environmental assistance began as a follow-up to agreed commitments at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 to assist developing countries in environmental development. A facility for assistance was established in 1993 and the total budget for this facility was expected to reach 0.5 per cent of the GNP by 2005. In 1999, DKK 3.2 billion was allocated and administered under three units: Danish Co-operation for Environment in the Arctic (DANCEA), Danish Co-operation for Environment and Development (DANCED) and Danish Co-operation for Environment in Eastern Europe (DANCEE). The strategy for environmental assistance for developing countries was developed under DANCED and targeted Danish Environmental Assistance (DEA) countries in Southeast Asia (Malaysia and Thailand) and Southern Africa (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa and Swaziland).

In 1998, DANCED provided support to a Danish consortium of universities to undertake a programme to strengthen their resource base for integrating environmental consideration in development planning and facilitating environmental assistance activities targeted at DEA countries by improving and supplementing on-going research activities. The pilot phase of this programme involved the development of relevant and extended curricula at Danish universities to support the traineeship of Danish students at DEA countries and was enhanced by activities such as educational conferences, continued education and increased mobility of students and faculty members.

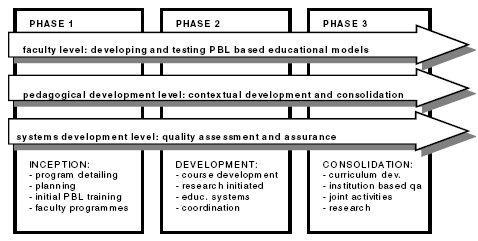

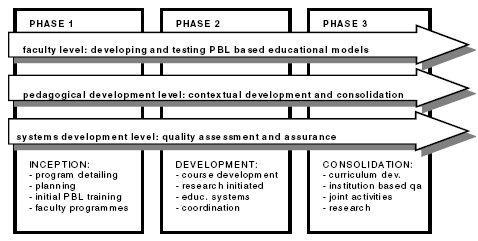

As the Danish consortium of universities concluded its pilot phase and entered into the consolidation phase, DANCED provided financing to support similar university consortiums in Malaysia, Southern Africa and Thailand. These three university consortiums were established at the end of 2000 and subscribed to similar goals in building the capacity of academic staff and students and developing a resource base in environmental management and sustainable development with more specific targets corresponding to priority areas within the respective countries. The consolidation phase of the Danish consortium of universities was geared towards working in collaboration with these newly established consortiums to support their respective programmes.

The Malaysian-Danish experience

The Malaysian consortium of universities was established in August 2000 and comprised of four public universities: University of Malaya, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Universiti Putra Malaysia and Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. The objective of the programme was to improve the capacity of master programmes at these universities by developing interdisciplinary and problem-oriented course modules utilising case studies in the field of environmental management and technology. The project drew upon the resources available at the Danish consortium of universities primarily Aalborg University, Roskilde University and the Technical University of Denmark. The main activity under the programme was the collaborative development of twelve masters’ level course modules, which was supported by staff exchange and training programmes, collaborative research activities and interaction with stakeholders. The project was concluded in September 2003 after a 10-month extension period. Some of the main activities in relation to this capacity building experience are described below (MUCED, 2003).

Curriculum development

The core output of the project was the development of course modules based on problem-oriented approaches, which are now being used within masters’ level environmental programmes at the four universities. Twelve common course modules were developed collaboratively between academics from these institutions through a joint effort to utilise resources and expertise available at the respective institutions. The course and case development process was conducted through a series of workshops throughout the project period as well as on an individual team level basis where the course outline was defined and assigned to various team members. Teams consisted of between two to five members from the four local universities.

Relevant material were sourced through the numerous initiatives (study visits to Danish universities, the training workshop series, and the research components) and used within the modules. The physical process of collaborative work with Danish academics was however limited. This can be partly explained by the difficulties in coordinating such a work process between academics from different institutions in different parts of the world. Better information technology and communication tools may play an important role in enhancing the process of knowledge transfer. Malaysian academics were exposed to problem-based methodologies but there was a resistance to step out of “traditional” teaching methodologies. There are still institutional constraints in fully practicing problem-based approaches.

In general, the development of course modules that are collaboratively designed and developed can play an important role in providing curricula an international outlook as well as raising the overall quality, as these modules would be subjected to the educational requirements of all the institutions involved. However, defining commons goals in curriculum development between international institutions can be difficult due to a variety of reasons. For example, the socio-economic environment plays an important role in defining the direction of the national and institutional educational policy in a country and there can be very obvious differences between these needs in developing and developed countries. Similarly, institutions, even within the same country, have programmes that vary in structure, academic objectives and research priorities.

Study visits

Study visits are an integral component in developing collaborative frameworks between institutions in the transfer of knowledge and expertise. These visits can vary depending on the objectives of the visit and the overall scope of a programme. In the context of capacity development at institutions of higher education, some common goals are to explore areas for collaboration, new techniques and methodologies, and establish physical linkages between institutions where training and development can occur. Under this framework, 15 senior academic staff conducted two-week study visits that were aimed at gaining exposure in problem-oriented methodologies in teaching and learning, collecting relevant course material and developing potential areas of research collaboration with Danish counterparts. This was generally achieved although the objective to conduct co-teaching to provide the Malaysian academics hands-on experience in problem-based learning was not possible for all visiting academics. These visits were often shorter in duration than initially planned however obtaining good scheduling between academics and host universities can be a problem due to a variety of reasons which includes variations in semester dates and other schedules. An optimum visit must nevertheless satisfy a sufficient duration of time to achieve the objectives set out and fall within the constraints of available funding.

Prior to visits, sufficient time needs to be allocated for planning and developing the visits between both parties. Although, generally this happens, more scrutiny needs to be put on this to ensure a successful visit. An important part of the experience when visiting a foreign institution comes from intercultural exchanges. This is an important factor when the aim is to integrate foreign curriculum in local programmes. The point of departure in doing this successfully stems from being able to recognise differences in teaching and learning cultures and adapting them accordingly within local programmes and standards.

Training workshops

The training component of the project was developed to support capacity development of the academic staff at the universities. It was primarily aimed at providing hands-on training and academic resources for the course development process both on methodological approaches in teaching and learning, and specific areas of focus on environmental management and technology. Workshops were conducted on problem-based learning, teaching methodologies, and module writing specifically to assist team members in preparing their modules. In addition, short courses and workshops were organised with the participation of resource personnel from the Danish universities in the areas of Environmental Economics, Environmental Ethics, Environmental Impact Assessment, Environmental Modeling, Occupational Safety & Health, Solid Waste Management, Water Recycling & Reuse, and Water Treatment Processes. Over 60 academic staff from various Malaysian universities participated in this programme.

In general, these workshops facilitated an active exchange of information among local academics and Danish resource personnel in understanding the problems and constraints in a local context, comparing differences of these scenarios with that in Denmark and exploring new ideas and methodologies. As part of the project objectives, the participation of stakeholders were continually encouraged and these workshops were well attended by representatives from numerous research bodies, government institutions, industries, non-governmental bodies, community-based organisations etc. This also provided a valuable experience for local academics and initiated a multi-level stakeholder dialogue, which is recognised as an essential process of solving environmental problems. External stakeholders, especially non-governmental bodies and community-based organisations gained an opportunity to build their own capacities and a closer relationship with the universities was developed.

Overall, these workshops provided an excellent ground for capacity development and are an efficient solution in training a large number of personnel. By developing a relevant training programme, based on specific objectives, the collaboration with international trainers and resource personnel can effectively support international development of curricula and in research. These programmes can be more effective if they can be integrated within existing training programmes on long-term basis.

Research activities

Within the project, research activities were conducted to support the course development component particularly to establish case studies for the twelve course modules. Funding for research was limited, however existing research funding available within the Malaysian universities complemented overall research activities. A total of 29 local case studies were developed for these modules by local academics and 18 joint research projects were established. Only limited input on this was gained from Danish academics particularly due to limited funding available to establish joint projects, time constraints and scheduling to develop and coordinate these projects, and the overall focus of the project objectives and activities which was different between consortiums.

Collaboration between the consortiums was gradually developed and supported research networks between Malaysian and Danish academics as well as academics from the other consortium universities in Botswana, South Africa and Thailand. Seven research networks were established within the project period as follows, and represented the participation of 19 universities:

- Critical Comparative Environmental Impact Assessment

- Environmental Management Perspectives

- Public Participation in Environmental Projects

- Chemical Assessment of the Environment

- Management of Resources in Urban Areas and Industries, Focus on Nutrient Recycling

- Water Resource Management

- Energy Planning and Technological Development

These networks were aimed at supporting an active discussion between academics from the different countries in exploring research areas and methodologies, and applying these outputs to provide continued support to curricula and course development. These networks have in general have applied two different approaches: the “integrated activity approach” where research objectives are explored through many different approaches and the “comparative study approach” where the focus is on comparing similar case studies from different countries (LUCED-I&UA, 2004). Joint projects were carried out through the funding of master and doctoral students from Danish universities at the partner consortium countries. Due to funding limitations, reciprocal exchanges by Malaysian students to Danish universities have not been possible, however this will remain an area of opportunity for the future.

Although, the overall impact and extent of these networks is difficult to evaluate, it was generally felt that collaborative research experienced by Malaysian academics help promote the development of new research areas as well as new approaches, techniques and methodologies in local research projects. There has been a continued exchange of information and knowledge between these academics, which has contributed towards building the capacity and quality of academic programmes in Malaysia. As a result of these collaborative networks, at least 21 joint research papers between Malaysian and Danish academics have been published in international journals and proceedings from 2001 to mid-2004. The seven networks were in various stages of development at the end of the project periods and initial efforts have been geared towards strengthening and expanding the collaboration and sourcing for funding to sustain the networks. A critical factor that initially hampered this was a lack of coordination of research activities within the project documents of the various consortiums and lack of allocated funding for this purpose. Overall, funding will nevertheless be seen as a major obstacle to collaborative research in developing countries unless there is better coordination of activities between institutions, commitment towards collaborative research funding is institutionalised and a culture for collaborative research is developed.

Joint field courses

Joint field courses are intensive three-week problem-based courses that are developed collaboratively between Danish and Malaysian academicians. Three joint field courses were organised from 2002 to 2004 in Malaysia on themes ranging from public participation to environmental planning, management and regulation. About 25 to 30 postgraduate students from Danish and Malaysian institutions participate in each course, which consist of one-week of lectures supplemented with field trips and two-week group project work. In total 39 students from Malaysian universities participated in these courses. Joint field courses are a means to introduce innovative teaching techniques, inter-disciplinary and problem-oriented approaches, and intercultural learning both for students and educators from these countries (Wangel et al., 2003).

The planning process for developing and implementing joint courses is an important element in organising a successful course. Course material needs to be developed collaboratively as individual academicians or institutions may have different expectations for their students. In this respect, curriculum will also need to cater to both student target groups, as different educational cultures (Wangel et al., 2003) can become very apparent when students come from a variety of educational backgrounds and nationalities. To level the playing field, introductory courses on local culture and socio-economy, intercultural learning, field research techniques and methodologies etc. play an important role in preparing students for group project work on real-life case studies within a foreign setting. Language is often a barrier to intercultural learning and this is also evident for group project work where communication between students becomes essential (Bregnhøj, 2003). However, this was not a very apparent factor in Malaysia as students from Denmark and Malaysia have sufficient command of the English language.

Overall joint field courses were a useful and unique experience for student and academic staff development. The pedagogical approach of working on real-life problems is a challenging and rewarding learning process that was previously not experienced by Malaysian students and academicians. In addition, intercultural exchanges between participants often go beyond the classroom, which itself is an invaluable learning experience. The exposure of Malaysian educators to innovative teaching and field research methodologies play an important role in building the academic capacity of local institutions on an international level. As a result, two more courses were organized.

To sustain a working programme, joint field courses need to be integrated within normal study programmes at participating universities. This would further entail allocating sufficient credit hours and schedules as semester dates vary greatly at different universities. Universities also need to develop sufficient funding and resources, internally or externally, to support and strengthen these collaborative frameworks. Host universities also play an important role in building relationships with external stakeholders i.e. research bodies, government institutions, industries, non-governmental bodies, community-based organisations etc. to support curriculum and student project work process.

Traineeship and field studies (TFS) programme

The Traineeship and Field Studies (TFS) programme was one of the main activities of the Danish consortium of universities during its pilot and consolidation phase. The aim was to train Danish students in interdisciplinary and problem-oriented project work through field studies in one of the partner consortium countries. Both a local and Danish supervisor supervised students during their three to six month stay where students experienced working on real-life problems within the social and cultural limitations of a developing country. A total of 56 students from Danish universities completed projects in Malaysia from late 1999 to mid-2004.

The TFS programme had its greatest impact on the students themselves. The experience has been enriching in terms of developing intercultural skills, hands-on experience in the area of study and increasing new knowledge. On the local side, the co-supervision of students has facilitated a physical exchange of dialogue and knowledge between the local and Danish supervisors. This can be translated into joint publications, development of new collaborative research projects and networks, as well future student supervision.