|

III Lessons Learned by DonorsSwedish Experiences of University Support and National Research Development in Developing Countriesby Tomas Kjellqvist, Head of Division for University Support and National Research Development Department for Research Cooperation, SIDAAbstractThis paper describes the Swedish experience of research cooperation with developing countries. Sweden has been one of few donor countries that have acknowledged the need to strengthen research capacity at an institutional level, rather than granting training of individuals and research project support. Recently major actors in the donor community have rediscovered the significant role of science and technology for development. From the Swedish experience Sida (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) suggests three areas where universities and national knowledge systems need to be strengthened: Research Policy, Research Environments and Research Management. The first and the last require that donors cooperate to assist developing countries in their setting up of conducive mechanisms for research. External support for the strengthening of Research Environments should be aligned with National Policies and Research strategies both at national and University level. In Sida’s experience cooperation between universities in developing countries and Sweden has proved to strengthen both local research environments and international scientific information exchange. Introduction

The Millennium Goals and the quest to combat poverty before the year 2015 are among the greatest challenges that humans have tried to meet. Meeting these challenges requires mobilization of all possible resources, both in society and nature, in rich countries as well as in the poorest countries. Fundamental to efficient and sustainable utilization of these resources is good governance. One of the foundations for good governance is qualified knowledge about the limitations and possibilities that nature, politics and technology could offer. Such qualified knowledge is lacking in poor countries, both regarding indigenous knowledge production and the ability to assess and adapt external knowledge to local conditions. This lack severely hampers the informed decision-making required to make viable strategies to combat poverty. Experiences of Swedish research cooperation with developing countries

The arguments above were very much the motive to include knowledge as an essential part of development cooperation already when Sweden started Research Cooperation with Developing Countries in 1975. The two complementary objectives stated in the original policy for Research Cooperation are still valid:

The Swedish engagement in bilateral research cooperation has been a learning process. The first 10 years could be characterized by support to national research councils. An evaluation of this period showed that, in most cases, these bodies lacked the capability to make priorities of research based on scientific criteria. Decisions were merely political which did not safeguard the quality of the knowledge produced. A countermeasure during the next period was to strengthen research capacity through research training using the so-called sandwich mode, which is still in use. This modality differs from ordinary research scholarship systems that detach the student from the local context. In the sandwich mode students spend time at Swedish Universities for coursework, analysis and writing-up, while the empirical research is formulated with a local perspective and with data collected from the local context. At first, research students were identified among staff in ministries, at research institutes and at university departments. Over time it became obvious that training of researchers had to be supplemented with investments in research infrastructures and scientific equipment. To cater for needs of scientific information support to libraries, and archives, was included in the approach. The sum of these should contribute to the establishment of research environments that would be attractive work places for the researchers trained in the bilateral programs. Through these additions the support gradually became more institutional than individual. As a result, choices had to be made regarding the selection of grantees. At the beginning of the 1990’s a shift was made to favour more comprehensive support with the aim to inculcate research cultures at national public universities. The university as a researching institution was given priority before research institutes because of its connection to higher education. Supporting the university was regarded as more sustainable investments, with the possibility to engage in long-term processes that would lead to the establishment of local research training. The decision to support national public universities was contemporary with a movement of university reforms. In most poor countries the 1980’s had been disastrous to universities, in some cases through financial neglect, in others through political obstruction of the academic freedom. With democratization and liberalized economies came an increased demand from students and university teachers to improve the situation for higher education. The Swedish Research Cooperation was seen as a tool in this process and was aligned with the strategic plans that universities developed to guide their reforms. The main provision for support was that research should be part of the strategic plan and that university teachers should be given the opportunity to engage in research or research training. Although this is part and parcel of most university reform documents, practice has proved that there are many barriers for the researching university to materialise. According to the Swedish experience the main responsibility to overcome these barriers could be attributed to the levels of governance and management. The need for research must be recognised not only by the University management also by Government through appropriate ministries. The resources available for research must be governed through National Research Strategies that align with strategies for Development and Poverty Reduction. Furthermore, National Research Strategies must not be shopping lists, but rather be elaborated to a level where they are fundable and assigning missions for the actors in the National Research System. The Swedish Bilateral Research Cooperation for some years, with some difficulty, has tried to engage at the level of National Research Policy. Recently a number of international initiatives have placed Science, Technology and Innovation on the agenda. Hopefully this will facilitate the dialogue with governments and harmonisation within the donor community to encourage the development of National Research Capacity based on plans and strategies for Science, Technology and Innovation. The Swedish experience also has shown that a properly working Research Management is necessary at the level of research implementing organisations. This research management should safeguard that research conducted is in line with governmental and university strategies, promote that researchers generate own ideas of research topics, and assist researchers to attract funding from possible sources. The research management should also guarantee a properly working financial administration of internal and external research grants, and assist researchers to find proper channels for research outputs through scientific journals and to potential users in the public and private sectors. Sida has developed a number of instruments to establish and strengthen such units at universities, but this still remains a challenge to the Swedish Research Cooperation. The following sections of this paper will describe how the new Swedish Policy on Global Development emphasises the experiences made by Research Cooperation and the need to further elaborate the instruments that has been developed through the 30 years of Swedish Research Cooperation with Developing Countries. Research cooperation within the new aid architecture

The Government Bill 2002/03:122 Shared responsibilities – Sweden’s policy for global development passed the Parliament in December 2003. This Government Bill grasps the new opportunities provided by globalisation and strengthens Sweden’s international efforts in support of the

Millennium Development Goals. The Bill encompasses all areas of policy and proposes a common objective: to contribute to an equitable and sustainable global development.

Sida has also developed an internal document “Perspectives on Poverty“ that describes Poverty as being context dependent, with a multitude of causes, which calls for Poverty reduction strategies that arrange a number of specific interventions, of which research is one, into a holistic approach. In Sida’s interpretation of the new policy, the two perspectives and the eight central component elements are dependent on the context in each collaborating country, and the balance between them must be set in accordance with national strategies for poverty reduction and development. The development of domestic research is seen as an important tool for poverty reduction. In the Paris Declaration for Aid Effectiveness 2005, Sweden among other countries, has agreed to make Development cooperation more effective with an increased alignment of aid with partner countries’ priorities, systems and procedures and helping to strengthen their capacities. The emphasis on ownership and poverty reduction have always been a guideline for Swedish Research Cooperation, but the new Policy and the Perspectives on Poverty has called for a sharpening of the strategies for Research Cooperation and the tools used. The principle of aligning research cooperation with the university system in each country has been increasingly done since the 1990’s. Recent shift of emphasis in the international approach towards science and technology as essential for development and poverty reduction has opened new possibilities to extend this approach into the entire national knowledge system. This shift of demand also provides new opportunities for Sida’s old wish to harmonise with other research funding agencies. The policies and agreements mentioned above, together with other efforts to construct a new architecture for aid could be summarised as follows:

Research cooperation as part of poverty reduction and development cooperation: demand for and supply of knowledgeThe section below describes three aspects of the shift of demand for research in development cooperation, followed by a description of how Sida perceives that the domestic supply of research based knowledge could be strengthened. Demands for knowledgeDescribing Knowledge for poverty reduction is connected to a great risk of reducing knowledge to instantly demanded needs for know-how. Research based academic knowledge has a far greater potential than so. One of the main features is that it should always be subjected to quality control through peer review. Through this peer review domestic research links up with the international academic knowledge base, part of the Global Public Goods. A foundation for this body of knowledge is that it origins in the curiosity of researchers. Principles for academic freedom have been set up to safeguard that this curiosity should be allowed to work regardless of political conditions. In reality governance of research always puts number of restrictions and guidelines, of which some are derived from the situation in which a country finds it self. The following three aspects try to summarise some generalities that pertains to knowledge for poverty reduction in developing countries. Knowledge for empowermentThe lack of a domestic research based knowledge means that developing countries are badly equipped in international negotiations, which maintains a situation of dependency. Agreements within international bodies may pass without the effects or preconditions for developing countries are analysed. Major investments that need foreign technology may be done without sufficient knowledge to assess if the procured products meet the requirements. Domestic research has a potential for national empowerment in this respect. The development of domestic knowledge could also empower the poor through various mechanisms by the development of new procedures and products derived from research results. Also dissemination of research results through the educational system and other channels provide a general increase in knowledge that may benefit the poor. A sustainable knowledge economyGlobalisation has led to an increased emphasis on knowledge as one of the major factors in international economic competition. The previous neglect of domestic research from governments and the donor community has postponed the possibilities for developing countries to enter into such competition. Most developing countries have natural resources that could be refined to high-value products with knowledge and innovation, thereby contributing to economic growth. Unfortunately, most developing countries also has harder natural conditions than developed countries which means that knowledge is needed to safeguard that exploitation of the potential products is made environmentally sustainable. Increased demand for higher educationPopulation growth in developing countries has created an increased demand for higher education. Most countries show an increased number in the age cohorts that are potential university students. With economic liberalisation and increased democracy higher education has become seen as a lever for social mobility. This demand manifest itself in an increased number of students applying for university and the growing interest in establishing private universities to cater for this demand. Governments are now faced with the necessity to come up with regulatory mechanisms and innovative funding strategies. Research and research training at the public universities also get a new role as provider of academic staff, not only for their own faculty but also for the entire university system. Supply of knowledgeEach country has its own system for the supply of knowledge. These are products of different types of interventions throughout history and rarely a result of a comprehensive strategy. Reforms are often called for but diverging interests within the system and ignorance from external stakeholders contribute to a status quo. In this situation that has persisted for a number of years, Sida has assessed some interventions as crucial and to be of a kind that contributes regardless of future changes in the system. A focus on strengthening universities as the main bodies for research and research training provides a good foundation for the development of knowledge, human resources and experiences of knowledge strategies on a larger scale than a single research institute could provide. At least one research university in a countryThe combination of research, research training and undergraduate education makes the university stronger and more sustainable than individual research institutes and researching NGOs. Supporting the university to strengthen good research environments in many subject areas provides a foundation for future research and research training. Doing this within one university could facilitate multidisciplinary research as well as interdisciplinary. Dependent of the strength of the national university system, Sida choose different strategies to focus research funding. In a weak system funding would go to one university rather than diluting it to many weak universities. In countries with stronger systems, resources could be spent on the research environments with best potential. The idea is that each country should establish at least one researching university that could cater for the needs of the country and eventually become a resource for the creation of a more extended university system and for national innovation systems. Links to the international academic communityNo university is stronger than its links to the international academic community. Sida has chosen interventions that contribute to strengthen such links, both to international research institutes and through regional cooperation in networks and organisations. Research training could be conducted in collaboration with other universities, in the north or with more developed university departments in neighbouring countries. Collaborative projects between researchers interested in the same topic form another opportunity. Other interventions link up universities to the Internet for communication and access to international scientific journals and databases. Support that facilitates for researchers in developing countries to participate in international scientific conferences makes other links available. Also support to international and regional organisations that promote issues of higher education and research contributes to involve collaborating university in wider networks. Curiosity driven and basic research as foundations for innovation and policy-formulationSida’s opinion is that a researching university must have the ability to conduct curiosity driven, basic research to be able to respond to demands and strategies. Without this ability the university loose possibilities to act pro-actively and strategically. Instead it gets restrained to react to current funding opportunities which risk reducing the quality of research. Interest for research in the Development aid community is by tradition focused on demand-driven applied research of direct value for policy-making or project implementation. Recent trends focusing on innovation tend to emphasise the same end of the research spectrum, though with a more strategic and systemic approach. Sida’s support combines support for basic research as well as applied, and has mechanisms to promote curiosity driven research as well as capacity to respond to demands. Research cooperation as capacity building

Sida’s strategy to fund the basic prerequisites for research at universities has produced a number of research environments over the world that could contribute to development and poverty reduction. However, to realize this potential much more need to be done by governments and the development aid community.

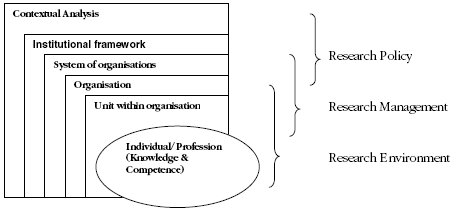

When a national Research Policy is formulated it takes into consideration the contextual analysis, reviews the institutional framework, sets up the system of organisations and defines roles of each organisation and how they relate to the system, institutional framework and context. Sida is challenged to find ways of assisting national efforts to improve national policies and strategies for research, science, technology and innovation. Some areas of intervention are described below Research Management refers to how a Research policy is implemented, within the systems of organisations, and within the organisations and their units. As Sida prefers to work with universities for research capacity building this area of intervention refers to support for efforts to strengthen management and management tools at university associations, universities and faculties. Building strong Research Environment has been at the core of the Swedish Research Cooperation. It includes of course the training of individual researchers, research supervisors and research coordinators, but also investments in the facilities necessary for performing research. The concept of research environment, in the context of Sida’s research capacity building scheme, refers to the levels of organisations, units of organisations and individuals. During the coming years Sida will explore new methodologies to assist countries in setting up and strengthening National Research Policies, develop research management and further strengthen research environments. The approach to development of these methodologies will be experiments based on experiences, looking for the opportunities given by advancements in each of the countries with which Sida collaborates. Hence, where there are advancements on the level of research policy, Sida will try to find the best way of supporting in alignment with the national context, where there are emergent research environments Sida will try to find the best way of supporting according to the local circumstances. Strengthening of Research management will be the most “forced” endeavour, as accountability and transparency are part of Sida’s strategic priority to combat corruption. Also, good research management is a prerequisite if developing countries should make the best use of what different donor agencies are offering. The best donor coordination would be the one executed by the universities who are about to strengthen their facilities for Research and Higher Education. Donor Experiences from Capacity Building Proposals Related to Knowledge Society Constructionby Finn Normann Christensen, Secretary-General, DANIDA/ENRECAAbstract

The Danish Bilateral Programme for Enhancement of Research Capacity in Developing Countries (ENRECA) has achieved good results in building public sector research capacity in developing countries at the project level. The experiences have also shown that it is difficult to integrate support for research capacity with the other parts of the Danish bilateral assistance programme and that the programme for capacity building predispose initiative by the Danish partner. It is also difficult to maintain the interest of Danish research institutions if the projects focus on capacity building rather than research. International Academic Exchange between Capacity Building and Brain Drain – the Case of the German Academic Exchange Serviceby Michael Harms, Head of Section Postgraduate Courses for Professionals from Developing Countries, DAADAbstract

Academic exchange requires mobility. For many generations, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) has enabled young and qualified students, graduates and scientists to leave their home country in order to spend some time at foreign institutions of Higher Education. Literally hundreds of thousands academics have been invited in the past six decades to study and to do research in Germany, many of them from Developing Countries. Although the very idea of “exchange” suggests a two-way traffic and possibly also a limited stay in the host country, there can be no doubt about the very real danger of a long term “skimming off” the academic and cultural cream especially of poor countries. International academic exchange between capacity building and brain drain – the case of the German academic exchange serviceAcademic exchange requires mobility. For many generations, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) has enabled young and qualified students, graduates and scientists to leave their home country in order to spend some time at foreign institutions of Higher Education. Literally hundreds of thousands academics have been invited in the past decades to study and to do research in Germany, many of them from Developing Countries. At the same time the DAAD has been able to support generations of German students, researchers and scientists in their drive to study and work at a foreign university in almost every country on the planet. Most of the exchange programmes are open to all disciplines and all countries, to foreigners and Germans alike, academic excellence being the main criterion for the selection of participants. With its various scholarship programmes the DAAD can support around 50,000 people per year with an annual budget of approx. EUR 250 million. Although the very idea of “exchange” suggests a two-way traffic and also a limited stay in the host country, there can be no doubt about the very real danger of a long term “skimming off” the academic and cultural cream especially of poorer countries. “In-country” scholarships

Universities in the South have successfully established regional centres of excellence, dealing with prominent issues of development in teaching and research. The “in-country/neighbouring country” fellowship programme of the DAAD has been initiated as early as 1962 by African partners. It offers fellowships on Master’s and PhD levels which enable highly qualified local students and students from neighbouring countries to make use of these training opportunities. The programme is operating on a fee-paying basis and thus strengthens the host institutions. It stimulates south-south student mobility and the emergence of regional teaching and research networks. The total number of scholarships granted per year under the “in country” scheme amounts to approx. 350. Forty-six training institutions in Africa, Latin America and South Asia are involved. Keep the links with the home university alive – the “Sandwich”-schemeA full PhD programme at a German university, including preliminary language training for foreign students, requires four years or even more. The formal requirements to obtain the degree in Germany (recognition of previous qualifications, compulsory additional subjects of study etc.), may extend the stay abroad without adding much value in scientific terms even further. Such a long absence from home can in some cases cause cultural and social alienation and reintegration problems and affect career prospects after return or – in the worst case – result in a somewhat long-term brain drain. The so-called “Sandwich” fellowship is offered as an alternative option of PhD training solely at a German university; students spend study phases both in Germany and in their home country. Their research is jointly tutored by German and local supervisors, the degree is awarded by the home university. As part of this co-operative scheme, funds are also made available for visits of the supervisors at each other’s university at various stages of the PhD-project, thus creating lasting personal and institutional links. A prominent alumna of this programme is the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate 2004, Professor Wangari Maathai of Kenya. She did part of her PhD-studies as a DAAD-fellow between 1967 and f69 in Gießen and Munich in Veterinary Medicine and subsequently earned her degree at her home university in Nairobi. Study programmes with special relevance to developing countries: postgraduate courses for professionals

For almost 20 years now, the German Academic Exchange Service has been supporting professionals from Developing Countries with an exclusive scholarship scheme. This fellowship programme enables young executives from southern (and in fact eastern) partner countries to obtain a master’s degree at a German university in courses with special relevance to the needs of developing and transition countries. The primary concern of the scheme is to further qualify junior management staff from various sectors – ministries and other government authorities, trade, commerce, industry, administration and NGO’s. Upon return, grantees are expected to go back to their home country and apply the knowledge they have acquired for the benefit of their countries development. In many cases, the participants go back to their established work-places and climb up the career ladder – becoming decision-makers and partners for future development co-operation. A recent tracer studies has revealed that the programme actually meets the high expectations; more than three out of four Alumni return at the end of their study in live and work in their native country or region; and out of these a high number hold senior management positions. Support cross-border educationAlmost all German universities on the aforementioned scheme work closely together with partner institutions in developing and transition countries. The DAAD has prompted and supported these close ties between institutions of higher education in the North and the South with a whole range of programmes (e.g. subject-related partnerships). As a consequence, many examples of cross-border education have evolved where modules or whole semesters are taught by one or several partners in the south. The DAAD regards these joint ventures as staff- and institution-building of a special kind; furthermore it is convinced that the importance and significance of cross-border education will constantly rise in the foreseeable future. Thus, it came not as a surprise, that one result of a recent conference on “Cross-border Education in Development Co-operation” organised by DAAD and HRK (German Rectors’ Conference) was the request of participants to position the topic of cross-border education and development co-operation more strongly also on the political agenda. By doing so, it is intended to create awareness and stimulate debates on the long-term implications of the new zeitgeist of the increasing market-orientation of higher education and research policy which is a potential hindrance of cross-border education. At the same time the conference participants agreed that joint ventures with partners at eye-level can be an effective tool against brain drain if all parties involved can agree on criteria of successful cross-border education by taking into account different approaches and goals in science and higher education. From individual to institutional co-operationAcademic exchange creates personal ties and “informal” working contacts between individuals. The structural impact of these relationships can be increased by transferring them into institutionalised co-operations. Since 1997, the DAAD supports German universities which enter formal relations with partner institutions from the south and propose joint projects. Funding is granted for mobility costs and to a limited extent for equipment and staff. The programme encourages the establishment of multilateral networks and south-south co-operation. Most of the 235 projects which have so far been supported combine the development of joint curricula, training modules and degree programmes with applied research; some typical examples are flood protection (China), reform of teacher training (Mozambique), rehabilitation of Agent Orange-affected forest (Vietnam), labour law (South Africa), sustainable agriculture (Cuba and Mexico), integrated watershed management (Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda), technomathematics (Sri Lanka, India, Indonesia, Ethiopia), regional planning (Myanmar), architecture of the tropics (Mali). Experiences and feedback show that institutional capacity building through subject-related partnerships can be a very effective way to open up a real perspective for returning researchers at their home institutions. Alumni

Last but not least, the DAAD regards strong and lasting links to its Alumni as an efficacious antidote against brain drain. Continued support for former fellowship holders by equipment grants, scientific literature and invitations to seminars and conferences can be described as a standard feature of the fellowship programmes of the DAAD. Furthermore, all ex-grantees can apply for a re-invitation scheme which gives them the opportunity to return to their host universities for shorter periods of further training and research.

|

||

|

To top of page |