|

Quality policy measuresIn Denmark, there is no single, nation-wide, quality approach, but common principles and measures at system level, and different approaches at both system and provider level. The Danish Ministry of Education has defined nine common principles/measures concerning the policy on quality issues:

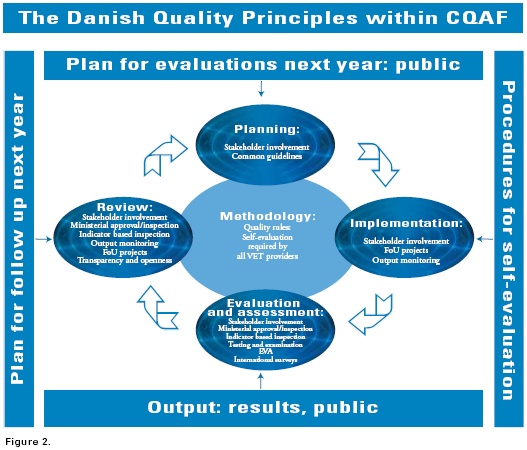

These measures apply to the entire Danish education system, but are given different weight, and take different forms, within the education system. The Common Quality Assurance FrameworkIn the following, these nine measures will be described within the framework of the CQAF model10, which is based on the quality circle. The model consists of four elements:

Core quality criteria have been identified for each of the elements. The criteria are presented as possible answers to specific questions, which are universal when reviewing existing policies in any VET system11. A number of questions have to be answered for each stage.

These questions, and the overall model, have formed the basis for a classification of the nine Danish quality principles; e.g. in the implementation stage, one of the key questions is “How do you implement a planned action on increasing the completion rate?” In the Danish VET system, one answer is “by initiating projects at the colleges aimed at supporting the individual learner and hereby increasing the overall completion rate”. In the review stage, another key question is “How do you organise feedback and procedures for change?” The answer in a Danish context could be: “by reviewing the results of projects aimed at increasing the completion rate at the college”. Figure 2 shows the classification of the Danish quality principles within the CQAF.

The various stages can only be separated analytically. In reality, the stages overlap, and the quality principles and measures described in this publication may cover several stages of the model. However, the figure gives an overview of how quality assurance and development are dealt with in the Danish VET system. Involvement of stakeholdersAs already mentioned, the involvement of stakeholders is a very important feature of the Danish VET system. The three main stakeholders are the learners, the enterprises and the social partners. The system is based on continuous dialogue, and on the idea that all the stakeholders in the system are able to contribute to the continuous innovation and development of VET in Denmark. In this way, the stakeholders contribute to all stages of quality assurance and development. Social partners One of the main objectives of involving the social partners is to ensure the relevance and quality of VET programmes in relation to the labour market. The trade committees are responsible for the continuous adaptation and development of the VET programmes. The committees monitor the skills development in the labour market, and recommend changes to existing programmes on the basis thereof. They may also recommend the establishment of new VET programmes, or the discontinuation of out-dated VET programmes. The role of the social partners is to ensure that VET matches the needs and demands of the enterprises and the labour market at both national and local levels. Another important aspect of the trade committees’ quality assurance is the approval of training places in IVET. The trade committees are responsible for approving and inspecting enterprises that want to take in trainees, on the basis of defined criteria. To be approved, an enterprise must have a certain level of technology, and a variety of tasks to be performed that will ensure the trainee a full range of activities and tasks corresponding to the qualification requirements of a skilled worker. Learners Furthermore, the Danish Ministry of Education initiates surveys among the trainees, e.g. in connection with major reforms, whereby the trainees are able to provide feedback to national VET policies.

Enterprises According to some observers of the Danish VET system, the overall need for independent external quality control is considerably reduced, thanks to the involvement of the stakeholders at all levels of influence13. Common national guidelinesThe overall objectives for VET are planned and laid down in legislation. A number of laws, regulations and guidelines lay down the aims, structure, content, competence levels, examination requirements, rules for complaint, teacher competences, etc., as common national standards. In IVET, these regulations and guidelines provide an overall framework for the programmes. Since 1991, the requirements relating to content have become less detailed, in order to make the provision of IVET more flexible and more adaptable to local needs and demands. For the last 10 years, there have been various initiatives aimed at making the IVET programmes competence-based. In 2007, a new reform was introduced, of which the objective was to change the orientation of all IVET programmes, focusing much more on competence and learning outcome, and all national regulations were revised accordingly. The trade committees were responsible for the revisions. The introduction of competencebased programmes should be seen in the light of the transition towards a lifelong learning system, in which formal, nonformal and informal competences are to be recognised. The transition towards competence-based programmes has taken place in CVET where approximately 140 joint competence descriptions have been drawn up by the social partners, in cooperation with the Danish Ministry of Education (2003). These are divided into approximately 2,800 different CVET modules of typically one week’s duration (from 1 day up to some weeks depending on the competences of the learner). The competence descriptions also provide a framework, within which the CVET providers are obliged to adapt their courses to the needs of local commerce and industry in order to meet the needs of the enterprises. Thus, legislation, regulations and guidelines provide framework standards for all VET programmes in Denmark, ensuring nation-wide homogeneity for the provision of VET as well as minimum standards and quality. The funding of innovation and development projectsIn the past decade, the funding of innovation and development projects (FoU) has been an important tool when considering quality assurance and development from the process side. Each year, the Danish Ministry of Education stipulates a number of political priority areas, which are described in two programmes. It is then up to the VET providers to formulate local or regional projects within these priority areas, and to apply for funding from the Ministry. Today, FoU projects play a minor role. However, FoU has been an important mechanism for the development of the Danish quality approach. In the early 1990s, pilot projects on quality assurance and development were initiated at a number of colleges. Afterwards, the results from these colleges were integrated in an overall quality strategy. The overall aim of the strategy was to improve and develop the VET that was provided, and to make the VET programmes more attractive. This was to be achieved by motivating the VET providers to integrate the principle of “self-evaluation” into their overall management philosophy, so that this would comprise an on-going, internal quality assurance and development, and a continuous evaluation of activities and results. So in order to promote the quality strategy at the colleges, quality became one of the FoU priority areas by the mid-1990s, and all colleges were able to apply for funding for quality assurance activities. Output monitoringOne element in the Danish quality strategy that has become increasingly important over the years is “output monitoring”. Whereas the focus in the 1990s was primarily on the process, and motivating the VET providers to set up quality assurance and development systems, the trend is now to promote quality by providing incentives. The VET providers have to fulfil specific policy goals in order to receive earmarked financial grants. In IVET, this new principle is called “value for money”. The Danish Ministry of Education specifies the priority areas, and offers the providers additional funding if they attain a number of goals within fields such as quality. The providers are encouraged to initiate activities within these fields. In 2003, the Ministry defined four priority areas concerning quality:

At the end of the year, the colleges have to document the local quality activities that have been initiated, and their results, in order to release the quality grants. The documentation has to be published on the institution’s website, and a report (questionnaire) must be sent to the Ministry. In CVET, a “supply policy” has been introduced vis-à-vis the CVET providers approved to offer joint competence descriptions. As of January 2004, the providers are obliged to draw up a policy stating how the institution will ensure that the region’s labour market needs will be fulfilled, within its budget target. This “Supply Policy” will be a precondition for the providers’ receipt of financial grants14. Internal evaluationThe “backbone” of the Danish quality strategy is selfevaluation by the VET institutions. All providers are required to evaluate their own performance and the courses they provide on a regular basis.

Quality rules All providers must document that they have a quality system matching the four phases of the CQAF model (please see figure 2, p. 14): Planning: the providers must draw up an annual plan for improvement, including how to increase the overall completion rate. Implementation: the providers must draw up procedures for methods of evaluation at specific levels and within specific VET programmes. These procedures must specify how users/ trainees/enterprises will be involved in the evaluations. Evaluation: the providers must report on the evaluation results within the priority areas stipulated by the Danish Ministry of Education and publish them on their website. Review: the providers must assess the results and draw up a follow-up plan, taking into consideration available resources and time. This follow-up plan should form part of the action plan for the following year. The results of these self-evaluations, including follow-up plans and strategies, must be publicised on providers’ websites. In IVET, providers are required to have15

However, the colleges are free to choose their own quality concept, and there is no national model or system which the individual provider is obliged to use. One of the reasons for this is that VET providers vary considerably in terms of size, organisational culture and the VET they provide, so they must have the possibility/freedom to adapt a quality strategy to the local needs and the local culture. In order to observe the quality rules, most colleges have set up a new function of “Quality Coordinator”, with particular responsibility for quality management. The quality rules for IVET also apply to the in-company training, whereby the trade committees are responsible for the ongoing quality assurance and development of the in-company training, in cooperation with the local education committees. However, the ministerial focus has been on the school-based part of the IVET programmes, as the in-company training is under the jurisdiction of the social partners. As a standard procedure, the Danish Ministry of Education monitors the completion and the employment rate for each VET programme and makes this the basis for a discussion with the responsible trade committee.

CVET providers are also obliged to set up a quality management system, formulate a follow-up plan and a plan for dissemination, and self-evaluate on a regular basis. However, since 2000, CVET providers have been required to carry out comparable evaluations of all the CVET programmes that they provide. For this purpose, a national self-evaluation tool16 has been developed, and now constitutes a compulsory element of the providers’ quality strategies. The aim is to measure both the participants’ satisfaction and learning outcomes, and the satisfaction of the enterprises whose employees have participated in CVET modules. It is a flexible tool that offers the possibility of inserting optional questions at regional and local level, so as to include other aspects of interest to parties such as the providers and the regional councils. The advantage of this system is that it is possible to establish quantitative aggregated data on quality in CVET at a national level. External evaluationAlthough internal self-evaluation constitutes the “backbone” of the Danish quality strategy, external evaluation is also essential, and is gaining importance. The focus is on how to improve the external, national evaluation of VET, based on the information given by the providers (please see “Next steps in the Danish approach to quality”). Ministerial approval, monitoring and inspection of

VET providers Secondly, the Ministry continuously monitors VET providers/ provision, by systematically collecting data on educational results (intake, trainee flows, completion rates, marks, employment, etc.) and finance. Thirdly, the Danish Ministry of Education undertakes a legal, financial and pedagogical inspection of VET. The process of inspection takes various forms, and is based on several inputs. These include desk research and analysis on the basis of selected data, and meetings and/or visits to selected institutions with specific colleges and trade committees. The following information is included in the Ministry’s inspection of quality at the vocational colleges: annual reports, websites, and data on completion rates, drop-out rates, grades, and transition rates to employment and further education. The inspection is not conducted by a specific national body. However, the Ministry is in the process of tightening up on monitoring, by introducing a new form of monitoring based on six quality indicators concerning output and outcomes. These indicators are:

The aim of the new system is to make the overall monitoring of quality in the Danish education system more systematic, and to provide a better foundation for the external evaluation of quality. The new system makes it possible to screen all educational institutions on an annual basis, and hereby identify institutions showing dissatisfactory results or quality in the training they provide.

This indicator based monitoring system will encompass the entire education system. Within the scope of VET, the indicators have been adapted to IVET and CVET. In IVET, all six indicators are considered relevant, whereas in CVET, only completion rates are relevant for the short CVET modules. So here, other indicators will be developed, most likely on the basis of the current national self-evaluation tool, with greater focus on the effect of the training. General external quality measuresA number of more general quality measures, i.e. those not only related to the VET sector, can be identified in addition to those mentioned above.

Testing and examination

Act on Transparency and Openness Evaluations by the Danish Evaluation Institute Each year, the EVA submits a plan of action outlining evaluations and other activities to be undertaken in the year to come. The Ministry ensures that the plan is in line with the objectives set out for the EVA. The EVA’s job is to evaluate education and teaching, whereas evaluations of educational institutions’ overall activities only can take place on prior approval from the Danish Ministry of Education. It should be mentioned that all evaluations comprise a self-evaluation performed by the 10-15 colleges normally participating in one of the approximately 12 evaluations carried out by the EVA every year. The EVA is also a knowledge centre on evaluation in Denmark. The EVA conducts research and surveys, develops methods of evaluation, and disseminates its knowledge among all stakeholders in the Danish education system. The EVA also cooperates and exchanges knowledge with evaluation institutes all over the world. Since 1999, the EVA has conducted a number of evaluations within the field of VET, most recently on quality assurance and development in IVET. These evaluations have led to specific actions in regard to the colleges involved in the evaluation, and to the Danish Ministry of Education. In their evaluations, the EVA forwards a number of recommendations targeted at the stakeholders in question, who are obliged to follow up on the recommendations. International cooperation and surveysIn Denmark, participation in international surveys, such as the OECD surveys, is also perceived as an important element of the national quality strategy. International surveys offer a valuable contribution to the evaluation of the quality of the Danish education system, insofar as they shed light on important indicators such as participation rates, proficiency levels, returns on investments, etc. Denmark is to participate in the OECD study on systemic innovation in VET from 2007-09.

The Copenhagen process and the cooperation on the CQAF have had an impact on the Danish quality policies in VET. They have increased focus on the use of indicators in IVET, and on the issue of a monitoring of providers and the quality of the education and training they provide. The Danish approach to quality within the CQAFThe Danish principles concerning quality cover different stages of the CQAF, and provide answers to different questions raised during the course of the various stages. In this way, the model helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the national quality strategy. In the case of Denmark, the strengths are the involvement of stakeholders at all levels of the system, the quality rules which apply to all VET providers, and the external evaluations carried out by the EVA. The weaknesses have been the lack of documentation showing that VET providers have actually implemented a systematic quality assurance system, and especially the lack of clear national quality indicators, thus resulting in a lack of basis for external evaluation (and inspection) in a highly decentralised system. However, the Danish Ministry of Education took the next step, by introducing six quality indicators for the entire education system in 2006. So when analysing the Danish approach to the quality of VET within the framework of the CQAF, the following overall status can be ascertained:

First wave from 1990 to 2000 The overall policy aim of the “first wave” was to establish a quality system for systematic self-evaluation and follow-up within framework governance – at provider level. This process was supported by continuous local and regional quality development, where the task of the Ministry was primarily to offer support and inspiration to local initiatives. The role of inspection and external evaluation was toned down until the late 1990s. The first sign of a change of policy was the establishment of the Danish Evaluation Institute (Danmarks Evalueringsinstitut – EVA) in 1999, as an external, independent body responsible for quality assurance and the development of Danish education and training.

Second wave from 2000 to ? This enables the Ministry to more actively identify quality problems at specific educational institutions and branches of the system. The annual resource report is the latest innovation within the Danish approach to quality in VET (see page 37).

CQAF indicators in a Danish perspective

Employability The disadvantage of this system is the lack of training places. Too few enterprises employ apprentices, especially because of changes in the business structure and work organisation. Today, many production processes are highly specialised, and furthermore, too expensive to slow down or leave to apprentices. Consequently, many enterprises do not employ apprentices, or cannot be approved as a training centre, because they provide an inadequate learning context. However, progress has been made remedying this situation. The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Integration have launched a number of campaigns and initiatives addressing the issue of training places. For example, the Ministry of Integration launched a campaign “100 training places within 100 days” especially aimed at second generation immigrants and employers, and there have also been campaigns within specific sectors aimed at increasing the number of employers taking in apprentices. Some progress has been made in general and in respect of these groups during the last few years.

Matching One of the main problems within the field of matching is how to make the VET programmes more attractive to young people. Denmark shares this problem with most European countries. Many young people opt for the general upper secondary education programmes, and do not find VET to be an attractive option. One of the Danish Ministry of Education’s main priorities is to find new tools dealing with young people’s values and priorities, and how to “shift” them in the direction of VET.

Access

However, the IVET system is still facing problems with the residual groups, and with trainees who drop out of an IVET programme. Immigrants find it particularly difficult to complete an IVET programme, and secure themselves an active status in the Danish labour market. As a consequence, a number of campaigns and initiatives have been launched focusing on retaining immigrants within the IVET system (see also page 33 on Employability). The CVET system is also highly flexible and modularised, and the increased integration with the IVET system will improve the possibilities of unskilled workers achieving the competency level of a skilled worker. In many ways, the system offers the opportunity for life-long learning. CVET focuses specifically on providing training for adults with a low level of educational attainment, and marginalised groups. Another main priority is to motivate and inspire adults to enter a Life Long Learning pathway. LLL is easier in theory than in practice. Thus, when it comes to achieving the Lisbon goals, and introducing quality measures as described in the Copenhagen Declaration, the Danish VET system offers a number of examples of good practice, despite the challenges it is facing. Moreover, the Danish approach to quality offers the awareness that quality assurance and development can be fully integrated in a VET system at both system and provider level. Footnote10) For a description of the CQAF, please see Fundamentals of a “Common Quality

Assurance Framework” (CQAF) for VET in Europe, by the European Commission,

Directorate-General for Education and Culture, 2004.

|

||

|

To the top of the page |